Looking for Uncle Joe

You couldn’t meet a kinder woman than Venera Sujashvili.

The owner of a simple homestay high in the Caucasus Mountains, she fusses about her guests from first light until late at night, making sure they are warm, well-fed and instructed in backgammon. So what’s a portrait of one of the world’s greatest mass-murderers doing on her dining room wall?

“Da, he was bad,” she answers in Russian.

“But he was part of my life, and I want my children to understand.”

Like many people in the former Soviet Republic of Georgia, a country of five million sandwiched between Turkey and Russia, Venera has a complicated relationship with Stalin. Few deny his brutality — his victims are said to number in the tens of millions — but many Georgians still take an odd pride in their most famous son.

“Sure, he was an evil brute,” their reasoning seems to go, “but he was our evil brute, a Georgian who changed the world.”

Stalin was born Iosif Vissarionovich Dzhugashvili in 1879, in the central Georgian town of Gori. He adopted the name Stalin — “man of steel” — only in his thirties.

His mother was a pious woman who took in washing to pay his way through the orthodox seminary in Tbilisi, Georgia’s capital. Years later, when her son wielded more power than any other human being, she still scolded him for being expelled and failing to become a priest.

His cobbler father, on the other hand, was a violent drunk who beat his family and died in an alcohol-fuelled brawl. As a child Stalin’s face was ravaged by smallpox, and an accident with a horse-drawn cart left one arm shorter than the other.

None of these obstacles — not even Lenin’s warnings about the “brutish bully” — stopped Stalin taking complete control of the Soviet Union. Historians are still arguing about how many millions of people died as a result.

An estimated ten million peasant farmers starved to death, including five million in the Ukraine alone, during his forced collectivisation of agriculture in the early 1930s. Millions served long sentences in Siberian labour camps and entire nations were deported from their homelands.

However, he transformed a backward, feudal state into a superpower and — despite a spectacularly incompetent start — turned the tide of World War Two against the Nazis.

Stalin’s personality cult was quietly dismantled after his death in 1953, but the party waited until the 1960s to go public with his crimes. Monuments to the Great Leader vanished by the thousands — including the world’s largest, a 17,000-tonne statue in Prague which took a month and 800kg of explosives to demolish. Each jacket button measured half a metre across.

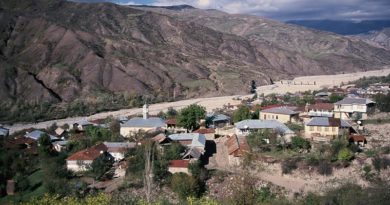

But there are still a few places where Stalin never went out of fashion. His birthplace is one of them, perhaps because Gori without Stalin would amount to little more than a crumbling fortress, Soviet-era factories and unemployed young men reeking of chacha, the local spirit.

The bus to Gori — helpfully identified by a portrait of Stalin on the destination board — dropped me in the centre of town, where a 17-metre Stalin statue loomed over grand stone buildings and a deserted Stalin Square. In the distance, at the far end of Stalin Avenue, a scaled-down classical temple appeared to shelter a precious relic.

On closer inspection, the relic turned out to be a two-room hovel. An entire district was razed and rebuilt to make this shack, Stalin’s birthplace, the town’s centrepiece. And the building behind it, with carved stone ornaments and an Italian-style bell tower, was Gori’s premier tourist attraction: The Stalin Museum.

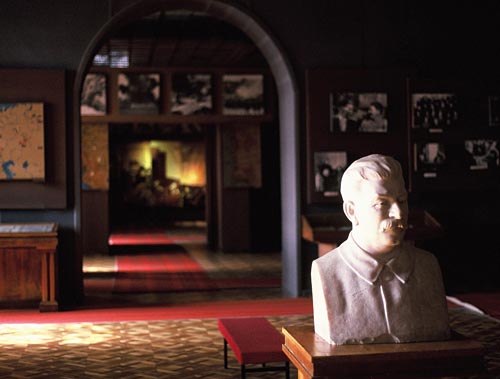

The museum was eerily quiet. I headed upstairs, past dozing security guards and a life-size marble Stalin. Light filtered through church-like coloured glass onto a parquet floor.

The school groups and hectoring guides have gone but otherwise little seemed to have changed since Brezhnev. Glass cases held rows of documents, grainy photos and clippings from Pravda, along with maps of Stalin’s exiles in Siberia and subsequent escapes, his disguises and police mug shots, and an exaggerated account of his role in the October Revolution.

Then a guide appeared and ushered me into a room crowded with gifts from foreign dignitaries: Red clogs from the Dutch communist party, a faded peace dove dedicated to “Giuseppe Stalin”, and a vase bearing one of the young Joseph’s poems: “Bloom, my nice country/Be glad Georgians homeland”. At least that’s what the translation said.

She also pointed out Stalin’s desk and a piano on which his children played at the family’s Black Sea dacha. She opened the lid to stroke the yellowed keys, then suddenly buckled at the knees and sighed heavily. At first I thought she had been overcome by emotion. But no.

“To speak English makes me very tired,” she said.

The creepiest room of the museum was empty except for Stalin’s bronze death mask, resting on a marble pillow and illuminated by a single dim spotlight. I was surprised the head of a man who had terrorised millions could be so small and wizened. And I’d had enough of the whole surreal experience.

Fortunately, an antidote to the museum’s one-eyed take on history is close at hand. When the guards aren’t looking, you can sneak into the train carriage displayed outside and plant your buttocks on Stalin’s private toilet.

At the nearby Museum of Military Glory I asked the curator what the citizens of Gori make of Stalin these days.

“They love him, but only the old people,” she answered.

“I don’t know why… maybe he had many mistakes, but he was strong.”

And after the bloodshed and economic freefall since the demise of the Soviet Union, you could forgive Georgians for admiring a leader who brought stability, kept a lid on ethnic tensions and made them feel they were part of a superpower.

When Georgia regained its independence in 1991, it spiralled into a series of chaotic civil wars involving nationalists, separatists, paramilitary groups, ethnic minorities and a dose of machismo.

Most disastrous of all was the war in Abkhazia, a breakaway region on the country’s northern Black Sea coast. Apart from the human cost — 10,000 dead and 200,000 refugees — Georgia lost its best beaches, its tourist industry, its only rail link to Russia and most of its exports. The result was a drop in living standards that was drastic even by post-Soviet standards. Once the richest republic in the Soviet Union, in the mid-1990s Georgia ranked among the world’s poorest countries.

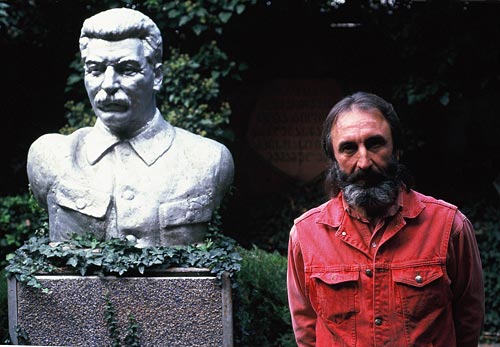

Perhaps the most bizarre stop on Georgia’s Stalin trail is a back yard in the bucolic village of Akhal Sopeli, where one man has spent decades creating a garden worthy of the Generalissimo.

Temuri Kunelauri is a quiet-spoken, self-effacing man with dark hair tied back in a ponytail, streaks of silver in his beard and a fondness for loud shirts. His garden is an odd place, a Stalinworld amusement park complete with swings, fairytale characters and a rusting Ferris wheel.

But the atmosphere as I tagged along with a group of visiting pensioners was one of reverence. I felt I was entering a holy site.

The group shuffled through a maze of courtyards, with Soviet busts scowling from the vegetation, tinkling fountains and red stars planted in the flowerbeds. A missile had all but disappeared under ivy, and a sheepskin portrait of Stalin was rotting away. Dampness and decay hung in the air.

I ran into Temuri in a large, corrugated-iron hall, where he was showing a stream of elderly visitors his collection of paintings, photographs and news clippings. We saw Stalin in oils at the Kremlin, Stalin posing with Lenin, Stalin’s likeness drawn entirely with words in the curling Georgian script. There were photos with Churchill and Roosevelt, Stalin pensive in the library, Stalin lighting his pipe. Between a stuffed deer and an electric guitar, a bookshelf was sagging under Stalin’s complete works.

Then Temuri led me outside and flicked a switch on a control panel. With a grinding of gears and clanking of metal, a golden statue rose from the greenery. It was — surprise, surprise — Stalin, one hand tucked under his jacket, a beatific smile under his moustache and a halo of light bulbs around his head.

One of the admirers turned to me and said, “He was a very great man. There was no one else like him.”

“Stalin took us from this,” said another, miming a peasant digging a field, “and left us with atomic weapons,” pointing to the overgrown missile.

The final stop on our tour was a vine-covered shed where, behind a black curtain in a velvet-lined room, a wax model of Stalin lay in a coffin, half buried in red plastic roses. An elderly gent whispered, “It took him eight months to make this. He even sewed the uniform himself.”

When I asked Temuri why he had spent half his life turning his garden into a Stalin shrine, he answered without a second’s hesitation: “Because I love him.”

I waited for the smile, the crinkling of the eyes, some sign of irony. There was none.

“I love him for the same reason you are here,” Kunelauri continued. “Because he was a genius.”

I opted for a diplomatic response: “Sure, he was a genius. But an evil genius.”

Temuri smiled and turned back to the faithful gathered around the coffin.

“An amateur from New Zealand,” he said.

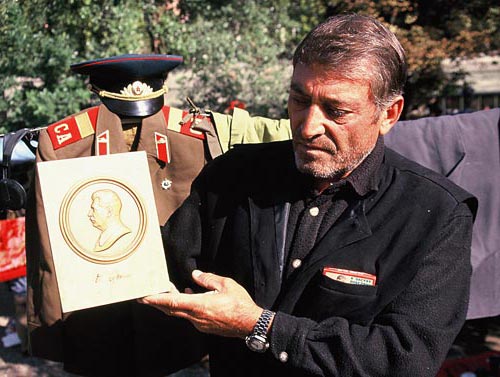

Down at Tbilisi’s weekend flea market, a stallholder who went by the name of Tarzan — a reference to the trees overhanging his stall rather than his physique — had the city’s best selection of socialist memorabilia. Soviet uniforms, badges, banners and, of course, mementos of Joseph Stalin.

A plaster bust, only slightly chipped, for five lari (NZ$3). Or how about a bronze relief of the Generalissimo on an imitation marble plaque for 50 lari? Instead, I bought several packets of cigarettes sporting a wartime portrait of Stalin studying a map, at 25 tetri (15 cents) each.

As Tarzan counted out my change, I asked his opinion of the world’s most infamous Georgian.

“Every era has its heroes and villains,” he shrugged, pointing to the branches shedding autumn leaves around his stall.

“The leaves come and go, but they are always the same. And so it is with people.”

First published in The New Zealand Listener in 2006. In mid-2010 the statue of Stalin was removed from Gori’s Stalin Square. Town authorities were planning to replace it with a memorial to the disastrous 2008 war with Russia, in which Gori was especially hard hit.

Where in the world is Georgia?

The Republic of Georgia is located at the eastern end of the Black Sea, sandwiched between Turkey, Russia and Azerbaijan. It has an area of 70,000sq km — making it a quarter the size of New Zealand, or roughly the size of Ireland — and a population close to 5 million.

Its people speak Georgian, which has a unique 2500-year-old alphabet, and trace their ancestry back to Noah. It is one of the world’s oldest Christian countries, and its most famous — or infamous — son is Joseph Stalin.

Georgia gained independence from the Soviet Union in 1991 and plunged almost immediately into civil war. Once the most prosperous part of the USSR, state wages fell as low as US$5 a month in the nation’s post-independence chaos.

In recent years, apart from a disastrous conflict with Russia in 2008, stability has returned and living standards have improved markedly. The Georgian government has worked to promote tourism, dropped most visa requirements and switched from Russian to English as its second language, making the country more accessible to foreign visitors.