The sound of metalwork

The Caucasus Mountains stretch from the Black Sea to the Caspian, a 5000-metre-high wall of rock between Russia and its southern neighbours Georgia and Azerbaijan. They boast Europe’s highest peak, dizzying ethnic diversity — the Romans took 140 translators on their Caucasus campaign — and some of the world’s most extraordinary hats. Their rugged isolation has also preserved traditions that vanished elsewhere long ago, like the metalwork of Lahic.

The village, high in the mountains of Azerbaijan, made its name in the 1700s when it supplied the Middle East with copperware and firearms. Little seems to have changed since then. Houses are still built by stacking stones between thick timber beams, an early form of earthquake proofing. Old women still squat beside the cobbled main street selling sunflower seeds while the men sun themselves, compare hats and gossip in Tat, the village’s unique language. And from every doorway echoes the staccato sound of tiny hammers tapping on metal.

Choosing a place to sleep in Lahic isn’t hard. Until recently the Ismailov family ran the village’s only guesthouse, named Cannet Bagi, or Garden of Paradise, for the apple and walnut orchards that surround it. It’s no luxury accommodation — guests sleep on mattresses on the floor of spartan rooms, and anytime but summer the nights are bitterly cold — but that’s more than made up for by the backgammon lessons and endless glasses of sweet tea. Best of all, the Ismailovs have a 300-year-old Turkish bath where guests can douse themselves in steaming water for hours.

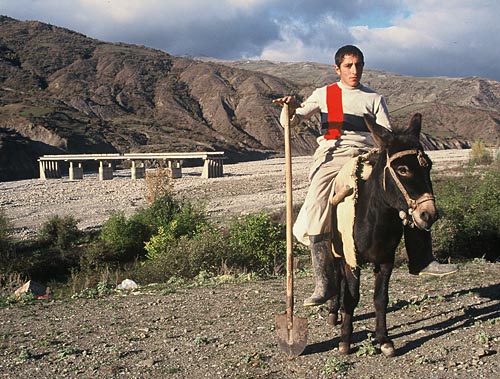

Garden of Paradise is run by a taciturn matriarch and her two sons, the younger of whom ends up being my interpreter. He explains he was named Intiqam, or Revenge, because he was born just as the conflict with neighbouring Armenia was heating up. The name and the staunch haircut contrast oddly with his thick eyelashes and impish grin.

Intiqam tells me the guesthouse sees 200-300 tourists a year, mostly in the spring and autumn. In summer it’s crowded with Azeris fleeing the heat of the capital, Baku, and in winter the road is closed by snow.

The beauty of Lahic is that it gets just the right number of tourists. Too few and you feel like a one-man freak show; too many, and hospitality evaporates. In Lahic just about everyone greets you with a hearty “salaam aleykom” — peace be upon you — and most stop to chat. It doesn’t take long before I’ve met the village maths teacher, the guys who run the antiquated telephone exchange, a Red Army veteran, and dozens of excitable children.

Lahic has a museum, a ruined caravansaray, the odd mosque, and some pretty scenery. However, the village’s real attraction is wandering the streets, poking your nose into workshops, holding muddled, multi-lingual conversations, and stopping for cups of tea.

On our first foray into the village, Intiqam introduces me to the wonderfully named Zeynalabdin Abdullayev, director of the Lahic Historical Museum. He explains that copper working started in the 15th century; at its peak, just over a century ago, more than 100 craftsmen were hammering out water jugs, bowls, dishes and trays. They were joined by potters, stone masons, saddle makers, cobblers, hat makers and gunsmiths.

I’m curious why an isolated valley, with no ore of its own, became a bustling metalwork centre.

“We are surrounded by mountains, so in wartime this is a quiet place. No one attacked and craftsmen could get on with their work,” Zeynalabdin says.

But today, he adds glumly, only seven blacksmiths and a handful of carpet weavers remain.

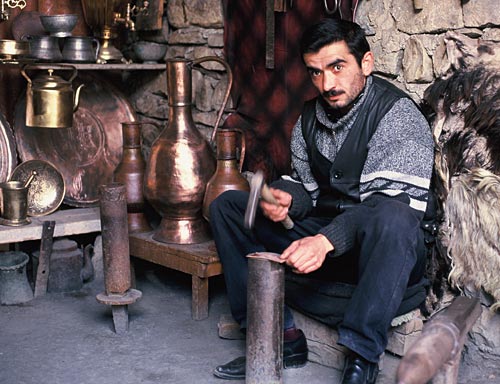

One such craftsman is Nazar Aliev, who ditched his $70-a-month job as a teacher to return to the family trade. His workshop is a single room off the main street, with anvils set into the dirt floor, copper stacked against white-washed walls, and racks of pliers and punches.

Hammering a design into an oil lamp, he says jugs and genie lamps — decorated with flowers, geometric patterns or characters from Azerbaijan’s national poems “about love and bad kings” — are his most popular wares. One lamp takes four days to make and sells for $40; in the tourist season he can earn $300-700 a month.

It’s a better living than teaching, but Nazar isn’t convinced life has improved since the collapse of the Soviet Union cast Azerbaijan adrift as an independent state.

“After independence it was good to sell things by myself. Before there were no foreigners and the state bought everything,” Nazar says.

“We thought life would be good, but it was better in the time of the USSR. Life was easy then. We had social security if you got sick or had no job, and we could travel all over the Soviet Union. Now we have no money to travel outside Azerbaijan.”

And until the road is fixed — the 20km drive into the mountains takes a hair-raising hour and a half and keeps many tourists at bay — Nazar will struggle to make a living, and the young men will keep drifting to the city. The government, blinkered by Caspian Sea oil, cares little about tourism or roads. Or that with every spring melt a little more of Lahic crumbles into the river.

In another workshop, Jusif Kamilov, chairman of the Lahic Craftsmen’s Association, is more upbeat. His shelves teeter with old samovars, water jugs, trays, bowls and candlesticks; his most popular item is the pilav tray, which sells for $70-$140. Some of his metalwork goes to the tourist bazaars in the capital, Baku, but most is sold in the village.

“One century ago our wares were sent to many other countries — the US, UK, Germany. Our handiwork was in museums around the world. Not now.”

But prospects are better now than in Soviet days when the Government sold 80 percent of the craftsmen’s work. Jusif’s gleaming 24-carat smile and holiday home in Baku suggest business is good.

“Today we can produce and sell by ourselves. The only problem is there are not enough customers. But they will come, insha’allah — God willing.”

First published in the New Zealand Listener, 2010.

Where in the world is Azerbaijan?

Azerbaijan is a country of about 8 million at the very southeastern corner of Europe – or the northwestern corner of Asia, depending on your perspective. Elevation ranges from almost 5000m on its northern border to below sea level beside the Caspian Sea; the climate varies from semi-desert to sub-tropical. It borders Russia, Georgia, Iran and Armenia, with which it has fought a bitter war since both countries regained independence in 1991.

Getting to Lahic

From Baku, the Azeri capital, several buses a day stop in the nondescript town of Ismayilli on their way to northwest Azerbaijan. From Ismayilli three buses a day brave the 20km, 90-minute trip to Lahic. Alternatively, a direct minibus to Lahic departs Baku’s chaotic 20 Yanvar bus station around 8am daily. In 2005 the five-hour trip cost about NZ$10.

Where to stay

When the author visited Lahic in 2005 the only place to stay was Cannet Bagi (Garden of Paradise), a homestay run by the Ismailov family. Accommodation is basic but includes the use of a historic Turkish bath. The rate for full board was about NZ$20 a night with meals such as goat kebabs marinated in pomegranate juice. Some travellers visiting Lahic since then report a price hike and a decline in hospitality. If that’s the case, you could try your luck looking for another homestay, or stay in one of Ismayilli’s modest hotels and visit Lahic as a day trip.