The Bone Church of Kutná Hora: Final resting place of 40,000 people or macabre tourist attraction?

Just imagine the problem: Your cellar is overflowing with human remains.

Skulls are stacked to the ceiling. You keep tripping over ribs. Everywhere you look unruly piles of tibias and fibias threaten to tumble to the floor like skeletal avalanches.

You can barely open the door for bones yet the head abbot is on your case, demanding more space so he can disinter a few more more bodies and sell off a few more plots in the cemetery.

What do you do?

One possible solution — though perhaps not the most obvious one — is that you could hire someone to bring order to the cellar by creating a series of macabre artworks.

Unlikely as it seems, that’s exactly happened 150 years ago in Kutná Hora, now a town in the Czech Republic about 80km west of Prague.

The curious problem faced by Sedlec Abbey had its roots in a pilgrimage to the Holy Land in the year 1278 by an abbot known only as Henry.

Souvenirs Henry brought back from his travels included a handful of earth from Golgotha, the hill were Christ is said to have been crucified, which he scattered in the abbey’s graveyard.

As word spread about the cemetery’s sacred soil it became a desirable final resting place for the pious citizens of Central Europe.

The Black Death (1346-53) and the Hussite Wars (1419-34) meant there was no shortage of bodies needing to be buried.

The cemetery was expanded and around the year 1400 a Gothic church was built at its centre.

As demand for space continued old graves were dug up to make way for the new arrivals, and the exhumed remains were placed in the church crypt.

The first serious attempt to create order came in 1511 when a half-blind monk, whose name is lost to history, was given the job of exhuming bodies and stacking the bones.

By the mid-19th century, however, the cellar situation was again out of hand.

No one’s exactly sure but by then it’s thought the crypt contained the remains of at least 40,000 people and possibly as many as 70,000.

Eventually, the Schwarzenbergs, the aristocrats who owned much of Bohemia at that time, had enough. In 1870 they hired a woodcarver named František Rint to put the bones in order.

Going by the results it’s clear Rint approached the job with great vigour and imagination.

Once he had stacked the bulk of the bones in four bell-shaped mounds he set about decorating the walls, ceiling and entrance, transforming the cellar into a macabre work of art.

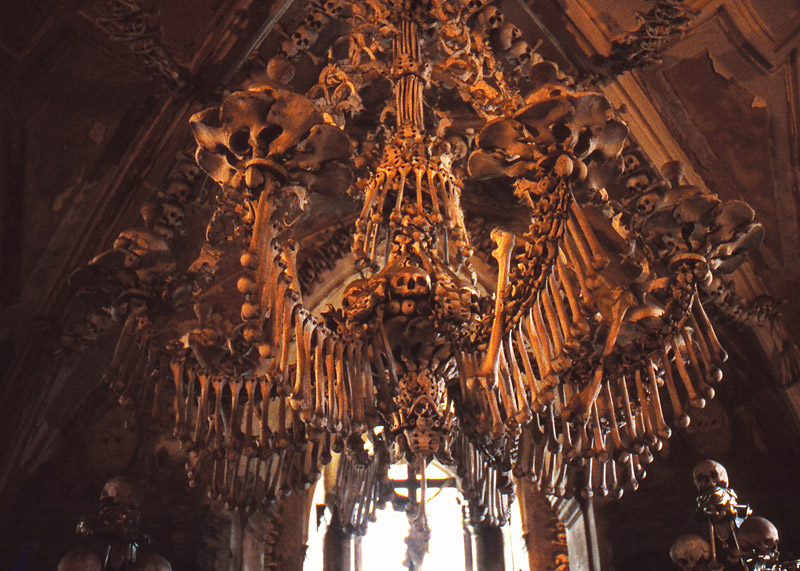

Rint’s morbid masterpiece is a massive chandelier made using at least one of every bone in the human body but he also created crucifixes, skull-and-crossbone arches, and a monstrance (a vessel used to contain the Holy Eucharist) in a niche beside the altar.

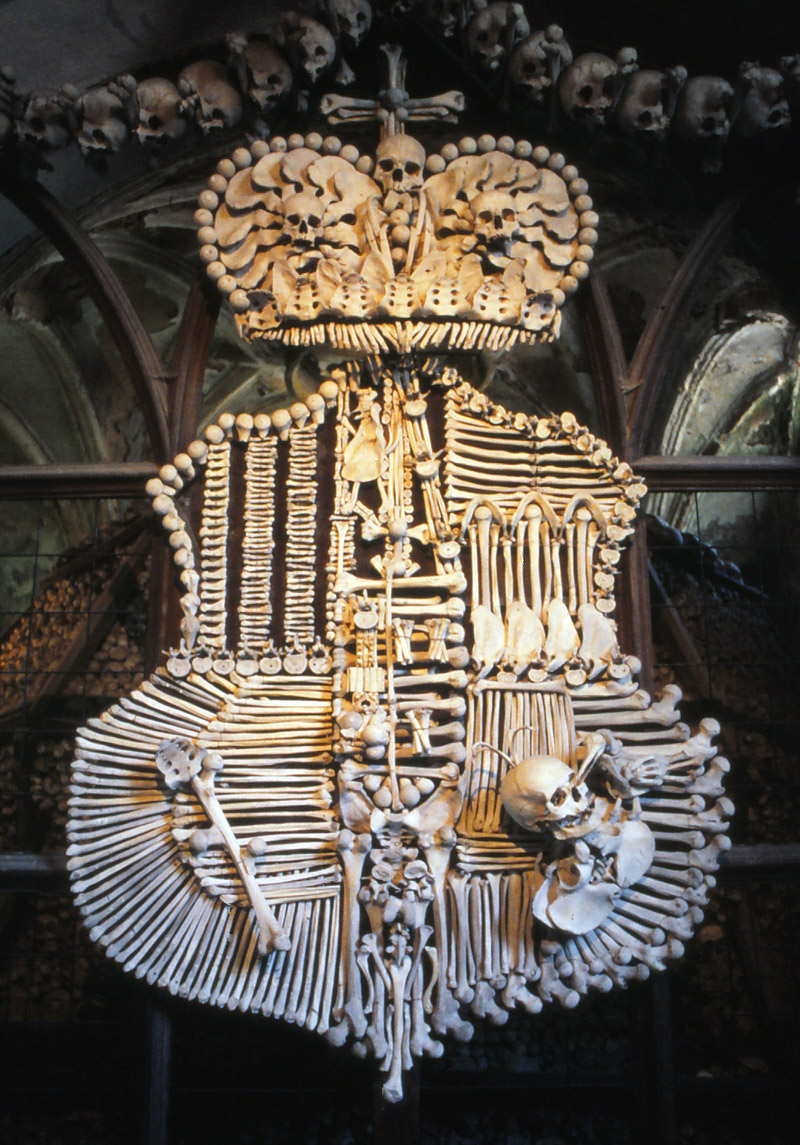

My favourite, however, is a super-sized, superbly detailed coat of arms of the Schwarzenberg family, including a raven pecking an eye out of a Turkish soldier’s decapitated head (a nod to the Schwarzenbergs’ military campaigns against the Turkish Ottoman Empire).

Rint even signed his name, in bones of course, on the wall by the cellar stairs.

The pitfalls of popularity

When I first visited in the early 1990s the town of Kutná Hora was a backwater and Sedlec Ossuary had yet to register on the tourism radar. (An ossuary, by the way, is a storage place for bones.)

The entry fee was about 5 crowns (NZ$0.30) and I had the place almost to myself, which made it even spookier.

It’s a very different experience these days, alas. As Prague has been blighted by over-tourism so too has Sedlec Ossuary.

It’s now one of the biggest tourist attractions in the country with, according to the Czech cultural information centre Nipos, more than 200,000 visitors a year until the Covid-19 pandemic put the brakes on mass tourism. That’s a lot of people for one small cellar.

One of the downsides of dark tourism sites is that they don’t always attract the best visitors.

After a series of skull thefts by unscrupulous souvenir hunters the ossuary was fitted out with proximity alarms which, though no doubt necessary, have further eroded the atmosphere.

The last time I visited Sedlec Ossuary a row of buses was lined up in the car park, there was a queue snaking through the cemetery, and any time someone leaned in too close to the bones — which was every minute or so — a deafening buzzer would sound.

Between the braying of the crowds, the selfies and blaring alarms, it was a far cry from the eerie stillness I remembered a few decades earlier.

Now I’m not saying don’t go to Sedlec Ossuary. I’m just saying choose your time. Try to get there first thing in the morning or go in winter. For God’s sake, don’t go at lunchtime in mid-summer.

At last report the ossuary entry fee was 60 crowns (about NZ$4). A photo permit cost 30 crowns (NZ$2) but that’s apparently no longer required.

Getting there and around

Trains leave Prague’s main station (Praha Hlavní nádraží) roughly once an hour. The trip takes about an hour and 20 minutes. You may need to change trains in Kolín.

There are buses too from Prague’s Florenc bus station; they are slightly cheaper but take longer and aren’t as much fun.

Kutná Hora isn’t the easiest place to get around because both Sedlec, where the ossuary is located, and the main train station (Kutná Hora Hlavní nádraží or Kutná Hora hl.n. for short) are a fair distance from the town centre.

Possibly the best strategy is to get off the train at Kutná Hora Hlavní nádraží, from where it’s a roughly 10-minute walk to the ossuary. It is signposted but bring Google maps or even better, because it doesn’t need data if you’ve loaded the map on your phone beforehand, maps.me.

It’s a roughly 40-minute walk through uninspiring suburbia from the ossuary to the town centre. Bring good walking shoes.

Pre-pandemic a minibus offered regular trips between the ossuary and the centre; that may still be running but don’t count on it.

Local buses exist but you can probably walk in the same time it takes to figure out the timetable, which would test even an expert in hieroglyphics.

Once you’ve seen the sights in the town centre, had a feed and tested the local Kutno Horská beer, you can catch the train back to Prague from Kutná Hora město railway station [město = town] near the historical centre. There’s no need to walk all the way back to the main railway station.

In case you end up having to ask for directions, Sedlec is pronounced sed-lets. In the Czech langauge Sedlec Ossuary is Kostnice v Sedlci.

Other attractions

Even without the ossuary Kutná Hora would be well worth a visit.

In the Middle Ages it was the biggest city in Bohemia after Prague, thanks to the enormous wealth generated by its silver mines.

A section of mine workings under the town is open to the public and accessed via the Czech Silver Museum [České muzeum stříbra] in the town centre.

Note that the tunnels were designed for mediaeval miners so they’re very low and narrow. It’s definitely not a good place for the claustrophobic.

The other top attraction in Kutná Hora is St Barbara’s Church [Chrám svaté Barbory]. With its sweeping, triple-pointed roof I reckon it’s the best-looking church in the country.

Work started in 1388 and wasn’t completed until the late 19th century. Delays included the previously mentioned Hussite Wars which forced the stonemasons to down tools for 60 years.

Named after the patron saint of miners, this Gothic masterpiece is rightly a Unesco World Heritage site.

More reading

The Wikitravel entry for Kutná Hora is a bit thin but has some good tips for getting to and around the town.

There’s plenty of ho-hum blog posts out there offering advice for visiting Kutná Hora but here’s a decent one which combines travel tips, cafe recommendations and Kiwi references.

You could also check out some great photos in The church of 40,000 corpses by BBC travel, or my other stories from the Czech lands: Bagpipes in Bohemia: A festival full of surpises, The strange case of the giant underpants and A pilgrimage to the birthplace of beer.