The strange case of the giant underpants

I’m not a souvenir kind of guy. I don’t buy miniature Eiffel Towers, Great Wall snow globes or Union Jack teatowels. I don’t even want a painting from Montmartre or a rug from Turkey’s Grand Bazaar.

I did, however, bring back a souvenir from a recent trip to Central Europe.

This small and at first glance unimpressive piece of fabric is, depending who you listen to, the product of a criminal act or an inspired political protest. It was the subject of a legal battle involving a famously foul-mouthed Czech president and an activist group whose name, when said out loud, sounds like an insult involving faeces.

This souvenir could, in theory anyway, put me in the awkward position of being in possession of stolen property. It’s also a symbol of public disenchantment and the age-old Czech tradition of using absurdity as a form of political resistance. But perhaps I should explain.

In September 2015 three members of the Czech art activist group Ztohoven disguised themselves as chimney sweeps and scaled the scaffolding surrounding Prague Castle which, as well as being a major tourist attraction, is the official residence of the Czech president.

Once on the roof they lowered the Presidential Standard — a flag bearing the national coat of arms, flown whenever the president is present — and replaced it with a giant pair of red boxer shorts.

Later that day the group released a statement saying, “Today we hung a banner over the castle for a man who is not ashamed of anything”.

The meaning was clear to any Czech who saw a giant pair of red underpants flapping in the breeze above Prague Castle.

The country’s first post-revolution president, the late playwright-philosopher Václav Havel, is still revered by many Czechs, especially the young.

Current president Miloš Zeman, however, is regarded by many as a buffoon with a potty mouth and an unfortunate habit of over-indulging in alcohol before public appearances.

Some citizens believe he is too close to China and Russia; others were embarrassed by his choice of words — in particular the Czech equivalent of the word usually regarded as the most offensive in the English language — when he was criticising the Russian punk protest band Pussy Riot during a television interview.

So the red undies were intended not only to poke fun at the president but also to highlight Mr Zeman’s perceived subservience to China and Russia.

Czechs would have also recognised the reference to the country’s communist past — before the Velvet Revolution of 1989, red boxers were among the few undergarments they could buy.

They were obligatory wear at mass gymnastic displays and came to symbolise the shortcomings of communism and all that was boorish about rural Czech society.

The giant underpants were promptly taken down and the three Ztohoven activists were arrested and charged with disorderly conduct, theft and criminal damage. The Presidential Standard, however, vanished and was presumed lost — until one day in July 2016 when I was sitting at a café in a provincial Czech town. This also happened to be the day the activists were due to go on trial.

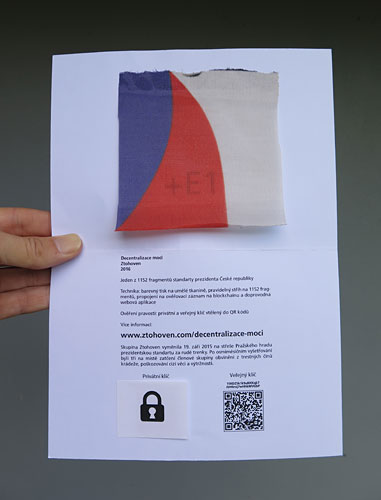

I was catching up with an old friend when we were approached by an earnest and well-groomed young man who introduced himself as a member of Ztohoven. After checking my companion was familiar with the story of the giant underpants he handed her an envelope containing a small square of fabric and a digital encryption key.

He said the group had cut the Presidential Standard into 1152 pieces, which they were handing out at random in towns and cities across the Czech Republic. The encryption key would allow my companion to claim a small sum of money in Bitcoins, a digital currency.

He went on to explain that police had claimed the group’s stunt had caused 35,000 Crowns (NZ$2300) in damage. Rather than paying reparation via the courts, the group had decided to distribute the same sum of money to randomly chosen Czech taxpayers. And then, with a furtive look over his shoulder, he disappeared.

My companion was delighted to go home with a piece of Czech protest history. I was disappointed to miss out — what a souvenir that would have been! — until I spotted a similar envelope lying on the road as I was walking back to my borrowed apartment. I don’t know if it was dropped accidentally or discarded by someone who failed to understand its significance, but the upshot is that I now own a piece of the Czech president’s flag.

I tried to contact the famously media-shy Ztohoven to ask why they had replaced the president’s flag with a pair of giant red underpants, then cut it up and given it away. The group didn’t respond to my requests for an interview but spokesman Petr Žilka did talk to Czech Radio.

He said the group was concerned about a tide of “very dangerous” legislation which was increasing the state’s control over individuals. Ztohoven wanted ordinary Czechs to think about their personal political powers and how they should be used. Voting in elections every few years was not enough, he said.

Ideally the group would have cut the flag up into 10 million pieces, one for each person in the Czech Republic, but that was impractical so the size of the pieces was determined by aesthetics, he said.

“The value of all the pieces is 35,000 Crowns which is approximately the value of the Standard stated by the police as damage we caused by stealing it. So we symbolically give it back to the people, to the taxpayers, as a remedy,” Žilka said.

The response of the Czech president’s office was blunt. Spokesman Jiří Ovčáček told Czech Radio the act of cutting up the flag was “a dirty trick” and likened Ztohoven to the Nazis, who had desecrated the Czechoslovak Presidential Standard more than 70 years earlier. His analogy — equating an act of Nazi occupation to a group of activists stealing a flag — further incensed the president’s opponents.

The case against the three activists continues to make its way slowly through the Czech legal system. In August 2016 a district court judge dismissed criminal charges against the trio and referred the case to the Prague 1 district authority to decide whether they had committed a misdemeanour. That ruling, however, was successfully appealed by the state attorney, forcing the case back to the district court.

Meanwhile, one piece of evidence — a small square of fabric cut from the Czech president’s flag — is on display on a bedroom wall almost 20,000km away in New Zealand. As a souvenir it’s unbeatable.

· · · · ·

The group’s name, Ztohoven, comes from the Czech expression “Jak z toho ven?”, which translates roughly as, “How can we get away with this?”. Said aloud, however, it sounds like “sto hoven”, which means “100 shits” in Czech.

The guerrilla art group’s protest against Mr Zeman is not unique. In 2013 artist David Černý built a giant purple hand with an extended middle finger and mounted it on a barge in the Vltava River, where it made a super-sized rude gesture towards the president’s office across the water in Prague Castle.

Postscript #1: Ztohoven in court

In April 2017, according to Czech Radio, the three Ztohoven activists received conditional sentences and were ordered to pay 8400 Crowns (NZ$550) for the flag and 55,000 Crowns (NZ$3600) for damage to the castle roof. The prosecutor had demanded 88,000 Crowns in damages for the flag and castle roof as well as non-material damages of 300,000 Crowns (NZ$19,500). The defence argued the trio’s actions were an expression of free speech underlining their disagreement with the stance of President Miloš Zeman.

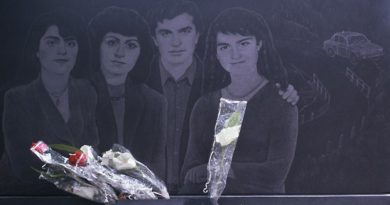

However, when the sentences were finalised in September 2017 all financial penalties were dropped, leaving the two surviving activists — Matěj Hájek and David Hons — facing only six-month conditional sentences (see the news report, in Czech). Tragically, the third activist, Filip Crhák, died in June that year from injuries he suffered in a motorcycle accident a month earlier (read the report of his death, in Czech only).

In the Czech legal system a conditional sentence is similar to a suspended sentence in New Zealand law. It means the defendant is punished for the offence only if he or she returns to court for any reason within a specified time, in this case six months.

Postscript #2: Underwear inferno

If you thought the story of the president’s underpants couldn’t get any stranger, you were wrong.

Another chapter unfolded on June 14, 2018, when President Miloš Zeman called a news conference and set the giant red boxer shorts on fire in front of assembled journalists.

Mr Zeman did not explain the stunt — apart from telling reporters, “I’m sorry to make you look like little idiots, you really don’t deserve it” — but, according to Czech media, it was supposed to symbolise the end of the era of dirty laundry in politics (see the BBC report, in English).

In the preceding months, especially during Mr Zeman’s close-fought re-election campaign, Ztohoven had continued to taunt the president with images of red underpants.

A spokesman for the president said he had purchased the giant boxers from the State Property Office for the princely sum of one Czech crown (NZ$0.06).

Postscript #3: Return of the flag

The Czech president’s flag is back.

In a tale already already bursting with intrigue, plot twists and plus-sized undergarments, the Presidential Standard has made a triumphant return to Prague Castle, the Czech Republic’s symbolic seat of power.

The flag owes its return to the election of new President Petr Pavel, a former NATO general who defeated populist billionaire Andrej Babiš in a second-round vote in January 2023.

Pavel’s first act as president was to return the Presidential Standard, which he unfurled from a balcony at Prague Castle in front of a cheering crowd as he took office on March 9.

It was a highly symbolic move by the new leader, who vowed not just to return the Presidential Standard but also to return standards to the presidency after years of scandal and embarrassment.

Former President Miloš Zeman, as described earlier, was known for his boorish manner and close ties to China and the Czechs’ former masters in Russia.

Babiš, a former Czech Prime Minister dubbed the Donald Trump of Central Europe, is a media and farming tycoon embroiled for years in allegations of defrauding the EU (he has since been cleared).

Pavel, on the other hand, was elected on a platform of steering the country back towards the West and returning dignity to the president’s office. An independent candidate, Pavel ran a campaign that evoked memories of the late, legendary President Havel. It probably didn’t hurt that their names are so similar.

Some media reports about the flag’s return state that the pieces were recovered and the Presidential Standard was painstakingly restored. Other reports say the flag was never cut up at all.

What is certain is that Pavel had been in negotiations with Ztohoven since January 2023 about the flag’s return, and that he plans to immortalise the story of the stolen standard and the giant underpants in a permanent exhibition at Prague Castle.

Burning questions remain, however. If the flag was restored why isn’t there a gap where my piece belongs? And where are the seams where the other 1151 pieces were stitched back together? If the flag was never cut up, then what is the tricoloured square of fabric on my bedroom wall?

Clearly, there is another chapter to come in the strange case of the giant underpants. Watch this space.

· · · · ·

With thanks to Jakub for help with translations and explaining the cultural context of red boxer shorts, Kristýna for the café catch-up that sparked this story, and Vera for alerting me to the flag’s return.

For more stories about the Czech Republic, check out A pilgrimage to the birthplace of beer or The Bone Church of Kutná Hora. You can also see my favourite photos of 1990s Bohemia in a post I’ve called Czechostalgia.

Loving your blog, PDG x

Thanks Therese!

Thank you for describing and posting this story in English. I brought the news article to my students of Czech language at one of US universities; we translated it from Czech to English in the class, and had a great discussion.

The presidential standard returned to the Prague Castle yesterday, March 9, 2023. Newly elected president received the pieces (not sure if all pieces or just some) from Czech citizens. The standard was restored, Petr Pavel brought it to his presidential inauguration festivities and returned it to the “people and the castle” when he greeted Czech citizens from the balcony inside the Prague Castle right after he was inaugurated. It will be displayed somewhere on the castle grounds including the story and the Castle visitors will be able to see it in the future.

Thank you Vera! That’s amazing. I didn’t think there could be a another chapter to the saga of the president’s underpants. I will have to update my blog 🙂