“We were starving”: How my aunties saved their family from famine

It was January 1945. The west of the Netherlands — including the cities of Amsterdam, Rotterdam, The Hague and my father’s home town of Leiden — was in the grip of Western Europe’s last famine.

Thousands had died already; by the end of World War II an estimated 18,000 people would starve to death.

Like many famines, the Dutch Hunger Winter was man-made. Food was already in short supply after five years of war when the country’s German occupiers blockaded the west of the country in reprisal for a rail strike called by the Dutch government-in-exile.

Many families faced a stark choice between starvation and going in search of food during the harshest winter in decades. Among the thousands forced to embark on a hongertocht — Dutch for ‘hunger journey’ or ‘hunger trek’ — were my aunties Do and José.

The sisters cycled from one side of the country to the other in subzero temperatures, risking their lives by using forged papers to get through German checkpoints to a rural hinterland where food could still be found.

And then, with bikes too laden with food to ride, they had to walk more than 180km through snow and bitter cold to get home.

This is Tante (Aunty) Do’s story as told to me in 2016. She died the following year, aged 95.

About the translation

This story was told to me in Dutch. I’ve made a few tweaks to improve clarity and reduce repetition. I’ve also added a few explanations but otherwise this is pretty much a word-for-word translation.

Do, pronounced ‘doe’, is short for Dorothea. Her younger sister was christened Josephine but known as José or Fien (short for Josephine).

Do uses the World War II-era slang term for Germans, Moffen, which doesn’t have an exact English equivalent — ‘kraut’ is the closest I can think of — so I’ve stuck to the more prosaic ‘Germans’.

When Do switches to German while telling the story about the guard at the bridge in Arnhem I’ve kept the original language but provided an English translation. I’ve done the same when she quotes the priest’s letter to parishioners in Dutch.

The Achterhoek (literally ‘the back corner’) is an agricultural area in the east of the Netherlands, near the German border.

The IJssel River (roughly pronounced ay-sell) is a branch of the Rhine that flows through the Netherlands. The IJssel Bridge the sisters crossed was one of the key battle sites of Operation Market Garden, the disastrous Allied military operation immortalised in the movie A Bridge Too Far.

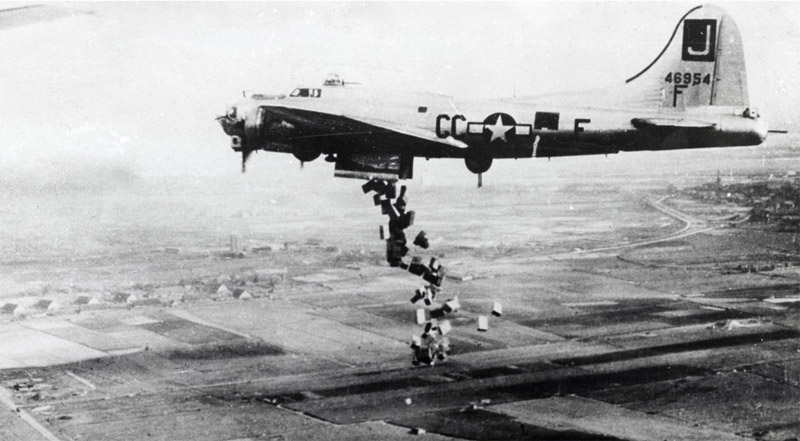

I have no photos of my aunties during the war. Cameras were rare and photography was risky if not illegal. Instead I’ve illustrated the story with images of the era sourced online.

The Hunger Journey

As told by Do de Graaf in September 2016

My sister José — we called her Fien then — and I were young women then. I was 21 and she had just turned 20.

We had a big family. Papa, who was a dentist, Mama, and seven children. I think the two oldest, Frans and Didi, had already moved out by then, though I’m not sure.

With so many children in our family, in a city like Leiden where there was very little to eat, José and I decided we had to do something.

We knew there was still food in the Netherlands but you had to go to the countryside to get it, not the cities. The situation was terrible in the big cities at that time.

We ate whatever we could get. There was a lot of surrogate food. There was of course no tea or coffee, for example, but there was surrogate tea and surrogate coffee. It was disgusting. But what else could you do?

Our mother and father became very thin because they gave any food they had to the children. Children got priority. In a photo taken for their 25th wedding anniversary you can see how thin they were.

We still had potatoes sometimes, because Papa got them from one of his patients. You couldn’t really get rice any more. Meat you couldn’t get at all. It wasn’t even worth talking about. As for fish, occasionally a lady from Katwijk [a seaside town] would come by with a cart of fish.

Bread was surrogate bread, it was hard, disgusting stuff. But you had to eat. You couldn’t get anything. It was all imitation food.

So Fien and I, we said, “You know what we’re going to do? We’re going to visit Pastor van der Snoek”.

We knew Pastor van der Snoek was in the Achterhoek near the German border. He used to be a priest at the Hartebrug Church in Leiden but by then he was a pastor in the Achterhoek, so we thought we’d try him.

My sister Fien had a bike and I borrowed one from relatives on the Lage Rijndijk [a street in Leiden]. We went by bicycle. When you’re 20 or 21, you can do anything. You have so much energy and stamina.

Along the way, if we saw a house that was a bit out of the way, we’d cheekily ring the doorbell and ask, “Madame, could we have some food? We’ll pay for it straight away.”

There was still money at that time, there just wasn’t any food.

“Well,” said one lady who answered the door, “come inside girls”. And then we got some food and asked, “Madame, please, how much do we owe you?”

And she said, “No! We don’t want any money.”

That happened many times.

We carried on by bike. Eventually we arrived in Gelderland [a province in the east of the Netherlands] at the River IJssel. The IJssel was an important river so it was guarded by the Germans. You couldn’t just cross the IJssel Bridge. That wasn’t permitted.

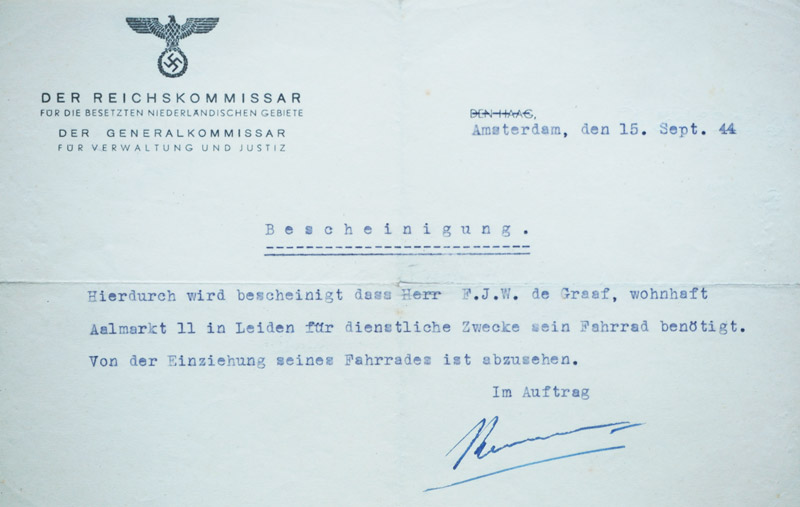

But we were prepared. Frans, our brother who was in the Dutch Underground, had made two false Scheine [travel passes in German] for us. Those passes said we were Rotes Kreuz Helferinnen [Red Cross helpers]. We were nothing of the sort.

So we came to the IJssel Bridge and we needed to get across but a German was standing there guarding it. He said we couldn’t cross, absolutely not.

“Nein! Gehen Sie zurück!” he barked. [“No! Go back!”]

Undeterred, we told him: “Aber wir haben unseren Onkel, unsere Tante auf der anderen Seite. Lassen Sie uns …” [“But our uncle and aunt live on the other side. Let us…”]

“Nein!” he said, before we could even finish.

“Aber wir sind auch Rotes Kreuz Helferinnen,” we replied. [But we’re also Red Cross helpers.]

And we showed him our papers. He took them and ducked into the basement of the building the guards were using. He had all sorts of lights and equipment in there so he could see if documents were forged. We were terribly afraid. We thought we’d be surely caught and then we’d go to jail. Or worse.

But after a while he came back out and said simply, “Ja, is gut”. [Yes, it’s fine.]

Frans and his friends in the Underground had done such a good job he didn’t notice our passes were fake.

So we were allowed across the bridge. There was another German on the other side but by then we were over the bridge and he let us carry on. That was the most dangerous part of the whole trip.

We carried on by bike and eventually we got to Waardesveld, but I’m not sure anymore. That’s near the German border. In any case, it’s where Pastor van der Snoek was. [Do probably meant Varsseveld, a village in the far east of the Netherlands.]

Then we visited Pastor van der Snoek. He recognised us because he’d been our priest in Leiden for a long time. He’d heard the situation was terrible in the cities. He sat down and wrote a letter for us:

Als een parochiale, de dames de Graaf uit Leiden, zijn we bekent. Als U kunt, wilt U ze dan helpen. Pastoor van der Snoek.

[Dear parishioner, the de Graaf ladies of Leiden are known to us. If you are able to do so, please help them. Pastor van der Snoek.]

Once we had our letter we started visiting all the farms in the area — it’s a very spread-out rural area — and whenever we showed farmers the letter they knew we’d been sent by the pastor.

A typical conversation went like this:

“What do you want?”

“Whatever you can spare. But we want to pay for it.”

One farmer said, “I’ve got a sack of flour here.”

“Yes please. How much can we pay you?”

“Just take it. You’re hungry.”

Another farmer gave us a side of bacon. Again we offered to pay.

“No, don’t pay,” he replied. “Pastor van der Snoek says so. Take it.”

That’s how it went the whole time. At one point we got a box of eggs. I put them in my backpack because we didn’t dare put them in our bike bags. But, and you can probably guess what happened next, a while later we were resting from cycling — I was so tired — and I leaned against a wall. I heard a cracking sound … a couple of eggs broken. We ate them raw on the spot.

And so it went on. Another farmer said, “I have some wheat, but it still needs to be milled”.

“That doesn’t matter,” we answered. “We can do that at home in a coffee grinder.” So we got a sack of wheat.

We stayed with a Catholic family and spent 10 days cycling around the Achterhoek, collecting a lot of food.

When we decided it was time to go back we couldn’t ride our bikes because the frames, bags and handlebars were so loaded with food. They were completely full. We couldn’t ride them. It was impossible.

“In that case,” we said to each other, “we’ll walk”. It was a few hundred kilometres.

And we were so cheeky — because that’s what you do when you’re 21 — that we hitched a ride on a German army truck. The soldiers saw us walking, two young women, and they stopped.

“Wo wollen Sie hin?” they asked. [Where do you want to go?]

“Wir wollen nach Leiden.” [We want to go to Leiden.]

They lifted our stuff onto the truck, those heavy bikes of ours with all that food, and they took us a long way, back over the IJssel Bridge. After a while they said they had to go another way, so we got off and carried on walking. I don’t remember exactly how long it took us.

It was below zero. It was January, it was ice cold. We saw children crying from the cold on the back of their parents’ bikes. But we’d been outside for days, we were used to the terrible cold.

I don’t remember where we stayed at night between Arnhem and Utrecht. I think we just rang people’s doorbells and asked if we could shelter or get a cup of tea.

What I can remember is that when we got to Woerden, that’s almost in Utrecht province, there was a large Red Cross tent where you could sleep. It was January, it was bitterly cold and dark early, but we could stay in that tent. Lots of people were in there already, all of them on hunger treks like us.

All night people from the Red Cross stayed awake and kept an eye on all those bicycles and carts loaded with food. There were hay bales you could sleep on. And that was good. At least you could rest. And all night people from the Red Cross walked around making sure everything was okay, that no bad things happened and that everyone’s luggage was safe.

The next morning we had to get out because the tent was being cleaned. We started walking again, from Woerden towards Bodegraven. Bodegraven-Alphen-Leiden, that was the route we followed.

I remember clearly that we got to Bodegraven and I couldn’t go any further. I was completely finished. I couldn’t go on.

Fien was stronger than me, she was a year and a half younger than me but much stronger. So I’d go and stand by a tree with my bicycle while Fien went ahead. Then she’d lean her bike against a tree 100 metres further up and come back and get my bike. And I’d shuffle along behind her. There was snow on the ground, it was bitterly cold.

After a while we saw a man — I don’t know where he came from, but he saw us plodding along. He took my bicycle and Fien took hers, and he walked all the way with us to Leiden. The whole way. I could still walk but I couldn’t hold the bike up any more. He walked with us all the way home.

By chance Mama was standing by the front door and saw us coming. Papa was inside working on a patient. Mama called out, “the children, the children!”

Papa tried to grab a couple of children and get them into his surgery because he thought something bad was happening and he had to bring the children to safety. But Mama meant that we were coming. It was quite a celebration.

And the gentleman who pushed my bike all the way to Leiden, we gave him a side of bacon before he had to walk back to Bodegraven.

Then everything we’d collected was carried into the kitchen. They couldn’t believe what they saw. I remember that house had a very deep, large cellar, and Mama quickly put anything that was perishable into the cellar. She made pancakes straight away with the flour. We were able to eat for weeks.

The bicycle that we’d borrowed was in pretty bad shape. I’d ridden it on tyres that were already worn through. We made up for it with a side of bacon for the owner. He was delighted.

The trip took us three weeks. We left on January 10 and came back on January 31.

When you are young you get used to the cold. It was terribly cold. Below zero. There was a lot of snow at times but mostly I remember the cold. But I also remember that we didn’t feel it much after a while. You get used to it. If you’re outside every day walking in the cold you get used to it.

On your own you can’t do something like that. But there were two of us and we spoke good German, we’d both learnt it at school. That made a difference. It helped if you could speak to the Germans in their own language.

Our parents were very afraid when we left. But they thought, “let the girls go”. We had to go because we were starving. It was terrible. But it all ended well.

And that’s how we survived the Hunger Winter.

Leiden was liberated on May 8, 1945, by Canadian troops and the Princess Irene Brigade, an exiled Dutch military unit.

If you want to learn more about Western Europe’s last famine you should read The Hunger Diary: My father and the Dutch famine. It tells the story of a diary my then 14-year-old father kept during the Hunger Winter of 1944-45.

| The dentist and the Nazi

Another of Tante Do’s many stories involves her father (my grandfather), who was a dentist, and a German officer. This is what she told me: One day a German soldier came to Papa with terrible toothache. If you’re a dentist or a doctor you can’t say, “You’re a German, I’m not going to treat you”. So he let him inside, treated him, and got rid of his toothache. And then the German said to Papa: “Sagen Sie, was wollen Sie? Ich kann Ihnen alles geben.” [Tell me, what do you want? I can get you anything.] The German thought Papa would ask for a kilo of butter or something like that. But Papa said, “Nein, ich brauche nichts. Nur…” [No, I don’t need anything. Except…] The German demanded: “Was? Was wollen Sie?” [What? What do you want?”] And Papa answered: “Die Freiheit.” [Freedom.] The German sighed and said: “Haben wir auch nicht.” [We don’t have that either.] So Papa treated him for nothing. And that’s what a dentist should do. |