Portmeirion of the south: How the most remarkable village in Wales was almost built in New Zealand

Visiting Portmeirion is like trying to go to a seaside town in Wales but waking up to find your driver has become hopelessly lost and taken you to Italy instead.

Portmeirion — which you could variously describe as a fantasy village, a gigantic folly or a museum of rescued architecture — nestles in a forested valley on the Welsh coast overlooking a broad estuary.

It’s a charming, eccentric collection of pastel-coloured buildings, baroque towers, piazzas, colonnades, cupolas and whimsical details, looking for all the world like it was plucked from northern Italy and dropped intact onto a corner of Britain.

If Portmeirion seems out of place among the UK’s monochromatic towns of brick and stone, just imagine how it would look if it had been built in New Zealand.

Yet that’s almost what happened.

Unlikely as it seems, Portmeirion’s creator Sir Clough Williams-Ellis considered building his dream village on an island in Auckland’s Hauraki Gulf before practical considerations — not least the difficulty of transporting his collection of rescued buildings around the globe — forced him to opt for a bay in Wales instead.

But before I can explain we’ll need to backtrack a few decades.

Sir Clough Williams-Ellis, an architect and environmentalist, was born in Wales in 1883. He served with distinction in World War I and was a fashionable architect in the inter-war era. When not designing homes he wrote and broadcast extensively about architecture, town planning and preservation of the rural landscape.

He played a key role in the creation of Snowdonia National Park but is best remembered for creating one of Wales’ most unusual, and enchanting, tourist attractions.

Chief among the legends about Sir Clough is that he searched the world looking for the perfect site to “embellish” with his collection of “rescued buildings” — historic buildings which had been slated for demolition — and after a decades-long search stumbled on an overgrown promontory just 10 miles from his home near the coast of Snowdonia.

Sir Clough started building Portmeirion in 1925. As word got around donations of historic materials, architectural curiosities and entire buildings flooded in.

He picked up other items at auctions and junk yards. A vat for boiling pig swill turned upside-down, for example, became part of a domed tower.

A large bronze statue of Hercules was placed in the central piazza and dedicated to the summer of 1959 “in honour of its splendour”. Even an old petrol pump was repurposed into an object of beauty.

When a 17th century North Wales mansion was demolished, much to Sir Clough’s horror, he bought the original ballroom ceiling for a mere £13. It cost him thousands to have it reinforced, cut up into pieces and reassembled at Portmeirion.

The end result was far removed from the functionalist architecture of the time which viewed buildings as “machines for living”. Instead, Sir Clough believed architects should provide for “the natural needs of soft little animals — us”.

From the outset Sir Clough designed Portmeirion to be financially self-sustaining with a hotel and holiday villas sequestered among its colonnades and pastel facades. It has also been the setting for movies and TV series, most notably the 1960s dystopian fantasy Prisoner in which a menacing beach ball named Rover plays the part of the prison guard and enforcer.

(I’m not kidding about the killer beach ball. You can watch the first episode on YouTube and see for yourself.)

It is often said that Portmeirion was based on the northern Italian fishing village of Portofino. That was denied by Sir Clough, though he did describe Portofino as “as an almost perfect example of the man-made adornment and use of an exquisite site”.

By all accounts Sir Clough was as eccentric as the village he created. In later years he was rarely seen without his “uniform” of yellow woollen stockings, knee-length breeches, matching yellow waistcoat and tweed jacket.

He declared the village complete in 1976 and died two years later aged 95. Sir Clough’s creation, and his life, had fulfilled his motto: “Cherish the past, adorn the present, build for the future”.

A Kiwi Portmeirion?

So how come Portmeirion, a village which seems out of place even in Wales, was almost built 20,000km away in New Zealand?

The answer can be traced back to the middle daughter of Sir Clough and his wife Amabel.

Charlotte Williams-Ellis, influenced no doubt by her father, developed an early interest in natural history.

While studying for a PhD at Cambridge University she met a Kiwi scientist, Whangārei-born Lindsay Wallace.

They married in 1945 and moved to New Zealand, where she forged a career initially in agricultural science and later as a founding staff member at the University of Waikato. Lindsay headed the Ruakura Agricultural Research Centre and was New Zealand’s Director-General of Agriculture.

Sir Clough and Amabel travelled to New Zealand a number of times to see their daughter and son-in-law.

During one of those visits, in 1948, they toured the country, studying the country’s architecture and meeting then Prime Minister Peter Fraser and leading town planners.

Sir Clough reported encountering great friendliness but also a “blazing and exhilarating row” with the Minister of Public Works, Bob Semple.

(Incidentally, during World War II Bob Semple designed the only tank ever built in New Zealand. It was made from corrugated iron on a bulldozer chassis and is sometimes unkindly described as the worst tank ever built.)

The argument “crackled in the newspapers for days with the utmost gaiety”, Sir Clough recounted in his autobiography Architect Errant.

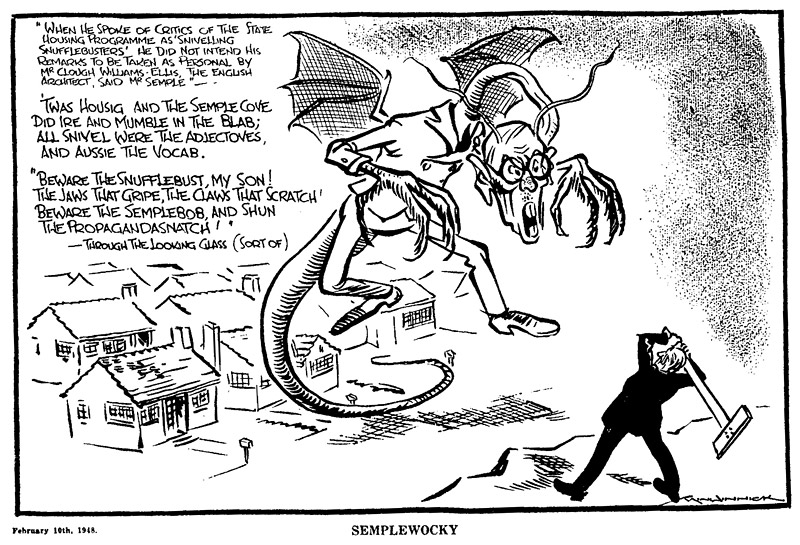

The row was immortalised in a cartoon in the New Zealand Herald in which Sir Clough uses an architect’s T-square to fend off a clawed, bat-winged “Semplewocky”.

On his return to Wales he recorded a series of what he called “poisoned shafts”, a critical commentary on New Zealand’s failure to preserve its architectural heritage. Those recordings were rediscovered in an attic and released as a CD in 2008.

Sir Clough was, however, as smitten by New Zealand’s natural beauty as he was appalled by its town planning.

He considered buying an island in Auckland’s Hauraki Gulf and creating an antipodean Portmeirion, where, as in Wales, the man-made and natural would complement each other perfectly.

In Architect Errant he described how he dreamt of “embellishing” the island, before reluctantly rejecting the idea as impractical:

“I had indeed one quite serious flirtation with a disturbingly attractive island off Auckland. I very nearly bought it, and have sometimes regretted not having done so — but I think I might well have had more regrets if I had, because being some 12,000 miles away, I could not really have cherished and embellished it as it deserved.”

Sir Clough doesn’t name the island in his autobiography but very few near Auckland have ever been up for sale. The most likely candidates are Rotoroa and Pakatoa, both privately owned islands east of Waiheke Island. His New Zealand descendants favour Pakatoa as the more probable.

Both were, however, owned at the time by the Salvation Army and not formally put up for sale until decades later, so it remains uncertain exactly which island he was considering. The only other private islands in the gulf are Ponui, the remote Rakino and, at that time, Brown’s Island.

Nor was the Hauraki Gulf the only place in New Zealand Sir Clough took a fancy to as a possible southern Portmeirion.

Rachel Garden, daughter of Charlotte Wallace, said her grandfather was also taken by Paku, a headland in “a lovely position” near Tairua on the Coromandel Peninsula where Sir Clough and Amabel spent a week camping in the summer of 1947-48.

However, Rachel believed her grandfather was concerned about Paku’s lack of a nearby population base to provide the visitors needed to make it self-sustaining.

Legend versus reality

Separating legend from reality is difficult when trying to work out how serious Sir Clough was about building Portmeirion in New Zealand.

He was fond of a good story and a fire at his home in Wales in 1951, which destroyed many of his records, makes the task of separating musings from serious plans even more difficult.

It seems unlikely Sir Clough would have built Portmeirion in New Zealand, given the cost of shipping buildings to the other end of the Earth. And he had in fact started work at the Welsh site some 20 years before his first visit to New Zealand.

However, had he bought a property in New Zealand, there is little doubt he would have “embellished” it in a similar way.

Perhaps he would have rescued colonial-era buildings slated for demolition and resurrected them on Pakatoa or Paku to complement their natural environment.

Alas, he thought better of it, and we had no eccentric collector of our own to save our vanishing architectural heritage.

If Sir Clough was appalled by what he saw in the 1940s, what would he have thought if he had witnessed the wholesale demolition of New Zealand’s heritage during the development frenzy of the 1980s?

The legacy lives on

Sir Clough was as dedicated to preserving the environment as he was to saving buildings. Perhaps his greatest achievement was persuading the British government to protect the highest peaks of Wales by establishing Snowdonia National Park.

Alarmed when a farm in Snowdonia was put on the market in 1936 for “lakeside development”, Sir Clough bought the property and donated the higher parts to the UK’s National Trust. Those peaks later formed the core of the first national park in Wales and the third in Britain, after the Peak and Lake districts in England.

Those ideals live on in Sir Clough and Amabel’s New Zealand descendants.

Daughter Charlotte Wallace, who taught biology at the then newly established Waikato University, helped set up the QEII Trust in 1977. The trust now protects 180,000ha of privately owned land of ecological and cultural significance around New Zealand.

She also fought the destruction of priceless native forests in Urewera, Pureora and Whirinaki, long before green causes became mainstream.

Kiwi granddaughter Catherine Wallace taught at Wellington’s Victoria University and has chaired ECO, a New Zealand-wide coalition of environmental groups, for many years. She has also campaigned for greater protection of the Antarctic.

Another Kiwi granddaughter, Rachel Garden, who, along with her husband Peter, is a director of Portmeirion Village, has fought mining in the Coromandel.

The Gardens also run a hikers’ campground in Snowdonia’s Nant Gwynant Valley on the lakeside land Sir Clough saved from development.

In yet another link with New Zealand, the campground is next to Pen-y-Gwryd Hotel, where a young Edmund Hillary stayed as he trained for his ascent of Mt Everest.

The hotel continued to host regular reunions for Sir Ed and his climbing companions until a few years before his death in 2008.

• For more reading check out Portmeirion’s official website.

Thanks for the article. The New Zealand cartoonist Minhinnick got Clough’s origin wrong: he was not an Englishman but a Welshman.

A core idea he had was that architecture and “development” should not spoil a site, and that natural landscapes should be respected and enjoyed.

He also experimented with low cost but warm, dry housing – and he an a co-authour wrote in 1919 about using materials to hand such as rammed earth and clay buildings to help solve the post WWI housing materials shortage.

Thanks Cath. Sounds like a man ahead of his time in many ways.

I’ve also learnt to never call a Welshman English, not even by accident!