Transnistria: How to visit a country that doesn’t exist

When is a country not a country?

That’s a perfectly reasonable question to ask if you ever find yourself in Transnistria.

This landlocked sliver of land in eastern Europe — about 230km long and at most 20km wide — has its own parliament, army, police force, border posts, flag, currency, national football team and all the other trappings of nationhood, but it won’t find it on any maps.

Nor will you find a seat marked Transnistria at the United Nations or a Transnistrian embassy in your own capital city.

That’s because, officially anyway, there’s no such country. Transnistria does not exist.

And that’s not even the only thing that makes this one of the strangest places in Europe. Transnistria is also a kind of Soviet time capsule where travellers crossing the border are sucked through a time warp into an era that ended everywhere else with the collapse of the USSR in 1991.

The break-up of the Soviet Union spawned more than a dozen new countries, some more ready for independence than others.

One of those was Moldova, a mostly Romanian-speaking republic sandwiched between Romania and Ukraine. Moldova’s new government moved quickly to forge closer ties with Romania and declared Romanian its official language.

But that didn’t go down well with Moldova’s Russian-speaking minority, many of whom live in a narrow strip of land on the eastern side of the Dniestr River. (Transnistria, also called Transdniestria or, in Russian, Pridnestrovie, means “across the Dniestr”.)

After months of escalating tensions a full-blown civil war broke out in March 1992.

About 700 people were killed before a Russian military intervention in July that year established a ceasefire, a Russian peacekeeping force and Transnistria’s de facto independence.

Since then Transnistria has been locked in a so-called frozen conflict, one of several around the former Soviet Union. No one’s shooting each other but they’re not putting down their guns either. About 1200 Russian troops are still stationed in the territory.

One of the curious side-effects of this frozen conflict is that it has preserved many aspects of the Soviet Union. The Transnistrian flag still displays the hammer and sickle, statues of Lenin still glower over town squares, and streets are still named after the heroes of the October Revolution.

If, like me, you started travelling too late to experience the USSR and you don’t have access to a time machine, Transnistria is the next best thing. Here’s my brief guide to travelling in a non-existent country.

Getting there

You can’t fly to Transnistria but you can fly or catch a train to Chișinău, the capital of Moldova, from many cities in Europe. (See my guide to Moldova, Europe’s least touristy country, for more information.)

From Chișinău’s chaotic central market buses leave frequently for Tiraspol, the capital of Transnistria. The fare in 2016 for the hour-long trip was 30 Moldovan lei (NZ$2.50) for the bus or about 50 lei (NZ$4) for a minibus.

Red tape

Some years ago the only way to visit Transnistria was on a transit visa if you were travelling between Ukraine and Moldova.

The only guarantee about that strategy was that you’d get a shake-down by bribe-hungry border guards — and good luck complaining to authorities who don’t officially exist.

By the time I visited the situation for travellers had improved immensely. An anti-corruption drive had cleaned up Transnistria’s borders and the government had even set up a hotline for reporting corrupt officials.

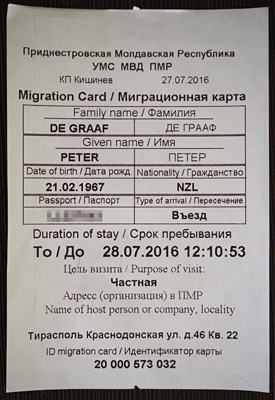

In 2016 you could get a 24-hour visitor’s permit for no charge at the border. All you needed was a passport with the correct documentation for Moldova or Ukraine, depending on which side you were arriving from, and the name and address of your accommodation if you were planning to stay overnight.

In theory you were supposed to have pre-booked your hotel but no one asked me for proof.

A smattering of Russian would be useful at the Transnistrian border; I had a kind bus driver to help answer the official’s questions.

At that time if you wanted to stay longer in Transnistria (up to 30 days) you had to register at the main police station in Tiraspol within a day of arrival. The process sounded tedious, with no guarantee of success, so I decided to make the most of my permitted 24 hours instead.

Since then, apparently, it’s become even easier to visit Transnistria. According to Wikitravel you can now get a 45-day visitor’s permit at the border, still without charge.

It’s not clear if you are supposed to have pre-booked accommodation but it’s a good idea to come prepared with the name and address of a hotel, wherever you are planning to stay.

Whatever you do don’t lose your permit, which is printed on a loose slip of paper. Getting out of Transnistria without it could be awkward.

There are no formalities on the Moldovan side of the border, presumably because that would amount to an admission by the Moldovan government that a border exists.

If you are transiting Transnistria from east to west there is a potential pitfall to be wary of. When you enter Transnistria from Ukraine you’re unlikely to get a Moldovan entry stamp in your passport because the Moldovan government doesn’t control that border, and without an entry stamp it will look like you entered Moldova illegally.

To avoid unpleasantness or a fine when you try to leave Moldova it’s a good idea to register with the Moldovan police once you arrive in Chișinău. See Wikitravel for more details.

The sights: Tiraspol

Who needs sights when the entire country is a bizarre Soviet time capsule?

There are, however, a few things worth looking out for.

Most of the attractions in Tiraspol, Transnistria’s capital city, are clustered around the western end of its main boulevard, called 25 October Street after the date of the Soviet Revolution.

You can’t miss the Tank Monument, a vintage T-34 tank honouring the soldiers of World War II, or as it’s known in these parts, the Great Patriotic War. The slogan painted on the tank, Za Rodinu!, is a Russian battle cry meaning “For the Motherland!”.

Nearby, an eternal flame burns at a poignant memorial to the 1992 war where the headstones portray every victim of the conflict’s first 24 hours.

Almost directly across the road, in front of the Transnistrian parliament, is a towering statue of Lenin with a red marble coat billowing behind him.

The city’s large covered market, Zeleny Market, is one of the liveliest places in what is otherwise a rather sedate city. You can find it just beyond the horseback statue of Suvorov, a Russian military hero, also at the western end of 25 October St.

On hot days locals head to leafy De Wollant Park, opposite the Suvorov statue, or sunbathe on the beaches along the nearby Dniestr River.

For another Soviet-era sight head to the other end of 25 October Street where a bust of Lenin scowls outside the Stalinist-style House of Soviets, now the city hall.

Since my visit Tiraspol’s authorities have even opened a tourist office and souvenir shop with English-speaking staff. You can find it opposite the Kvint shop on Lenin St, which links 25 October Street and the railway station. I’ll have more to say about Kvint later…

Bendery

My 24-hour permit gave me time to check out only one other city, Bendery, a short trolley-bus ride from Tiraspol.

Transnistria’s second city has a more traditional tourist attraction in the form of a 16th century Turkish fortress which saw heavy fighting between Ottoman Turks and Russians.

Part of the fortress is still used by the military — the border is only a few hundred metres away — but the rest is dedicated to displays of historical weaponry and the like.

Note that it’s not a good idea to point a camera at anything resembling a Russian military post, even if it is right next to a centuries-old fort.

Bendery bore the brunt of the fighting in 1992 and some buildings in the city centre still show the scars.

Bendery also boasts a number of museums I didn’t have time to visit, such as the Memorial Museum of the Bendery Tragedy, focusing on the 1992 war, and the irresistibly named Museum of Revolutionary Fighting and Labour Glory of Railwaymen. All displays are in Russian.

Accommodation

When I visited Transnistria in 2016 accommodation options were limited.

Unexpectedly, the capital, Tiraspol, has a backpackers’ hostel run by an American ex-pat who also offers Soviet-themed tours. I originally booked a night at Tiraspol Hostel but, oddly, the owner wouldn’t give me a street address, insisting that his driver pick me up.

When the driver didn’t show up I booked into the Soviet-era Aist Hotel instead, which is well located next to De Wollant Park and overlooks the Dniestr River. For 200 Transnistrian rubles (about NZ$20, slightly less than the hostel) I got a room with a balcony and a river view.

For God’s sake don’t stay at the Aist if you are looking for comfort or facilities (there isn’t even a restaurant for breakfast). If you want a genuine Soviet experience, however, it’s hard to beat, from the broken-down bathrooms, threadbare synthetic sheets and garish décor straight out of a 1970s LSD trip. It’s fabulous.

The only thing that wasn’t Soviet was the receptionist, who was obliging and even spoke a few words of English. (See also my review of best and worst hotels of 2016.)

Since my visit a few more accommodation options have sprung up in Tiraspol, including Lenin Street Hostel (centrally located on Lenin Street, between the railway station and October 25 Street), which looks promising. The owners also run Red Star Hostel and Camping on the city’s outskirts.

Money

You can exchange major currencies for Transnistrian rubles at any of the myriad exchange booths around Tiraspol. It’s a mystery why there are so many because, when I visited anyway, they all offered the same government-sanctioned rate.

Since 2018 the official exchange rate has been set at 16.1 rubles to one US dollar.

Note that it’s almost impossible to exchange Transnistrian rubles outside Transnistria. This is perhaps not surprising given that the currency officially doesn’t exist.

You need to spend all your rubles, or change them back into another currency, before you leave.

Transnistrian money makes a curious souvenir. The smaller kopek coins are metal but the higher values — 1, 3, 5 and 10 rubles — are made of a composite material on a fibre core.

As far as I know these are the world’s only plastic coins.

Postage

One of the joys of visiting a place like Transnistria is sending your mum a postcard from a place she’s never heard of. There is a catch, however: Transnistrian stamps are not recognised by the Universal Postal Union. That means if you want your postcard to reach its destination you have to stick on Transnistrian and Moldovan stamps.

Shopping

No one goes to Transnistria for the shopping but the country offers a few quirky souvenirs, like the plastic coins mentioned above, and one world-class product at a ridiculously low price.

Founded back in 1897, Kvint was the leading distillery in Moldova in Soviet times but ended up in Transnistria after the 1992 war.

Today Transnistrians rightly consider Kvint brandy one of their great national treasures. The distillery is depicted on the 5 ruble banknote and its award-winning, 50-year-old Prince Wittgenstein brandy is said to be one of the world’s best.

Even Kvint’s standard three-year-old brandy is superb and, for western travellers anyway, ridiculously cheap at 2 euros (NZ$3.40) for a 250ml bottle.

The great tragedy of backpacking, of course, is that there are only so many bottles you can carry without developing a hernia.

Kvint is an acronym for Kon’iaki, vina i napitki Tiraspol’ia (cognacs, wines and beverages of Tiraspol). The labels state that Kvint is made in Moldova because alcoholic beverages must declare their country of origin — “Made in Transnistria” wouldn’t cut it because it’s not an officially recognised country.

Kvint was privatised in 2006 and is now owned by Sheriff Corporation, which owns just about everything in Transnistria.

Sheriff: The company that owns everything

It would be unfair to suggest that Transnistria is some kind of unreformed communist backwater where the government owns everything. Most businesses are in fact in privately owned — it’s just that one company owns almost all of them.

Sheriff Corporation was founded in the 1990s by ex-members of the Soviet secret service with close ties to former president Igor Smirnov. In exchange for supporting the government, Sheriff’s founders were given a special deal on taxes and import duties.

The company now monopolises many facets of the Transnistrian economy, owning most of the country’s supermarkets and petrol stations as well as a TV channel, a publishing house, a construction company and a mobile phone network. Sheriff also owns the national football team, a NZ$300 million stadium and the country’s only five-star hotel.

The company’s founders have since fallen out with the government but Sheriff and Transnistrian politics remain inextricably intertwined.

International recognition

If you get into strife in Transnistria you won’t be able to go to your home country’s embassy for help. Even Russia, Transnistria’s main backer, doesn’t recognise its independence, though the Russians do have a consulate on 25 October Street in Tiraspol.

Transnistria is recognised only by a handful of other states which don’t officially exist — Sahrawi in northwest Africa, and Abkhazia, Artsakh (formerly Nagorno-Karabakh) and South Ossetia in the Caucasus. The United Nations considers Transnistria to be part of Moldova.

More reading

Unsurprisingly, given that it’s such a peculiar place, Transnistria has inspired some excellent travel bloggers and vloggers. Standouts include the highly entertaining Welcome to Soviet Wonderland! by Bald and Bankrupt, the more prosaic My Visit to the Breakaway Territory of Transnistria by Wandering Earl, and The best things to do in Tiraspol, a useful blog with great photos by a self-described “geeky and introverted” cultural anthropologist from the Netherlands.

Hallo Peter, nice and interesting to read ! Have a good trip .

Thanks Winfried! Glad you liked it. Hopefully I will see you again soon in Holland.

What an interesting story Peter. I vagely remember about it before ( from you ) Well done