Former Yugoslavia in pictures

| Travel in a time of coronavirus I started this blog as a celebration of our crazy, fabulous planet, but with Covid-19 closing borders for months, possibly years, any new adventures are on hold for the foreseeable future. So, in the meantime, I’ll be delving into my travel diaries and scanning my old 35mm slides to bring you some stories and photos from the past 25 years. |

My first trip to Yugoslavia, back in 1989, was almost an accident.

I’d been travelling around Turkey and I needed an inexpensive way to get back to Western Europe — I’d hitchhiked through Greece and planned to stick my thumb out again once I reached Austria — so a train the length of Yugoslavia was just the ticket.

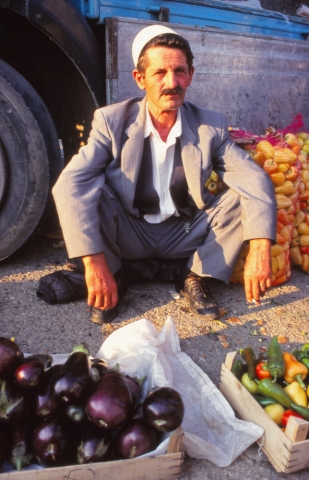

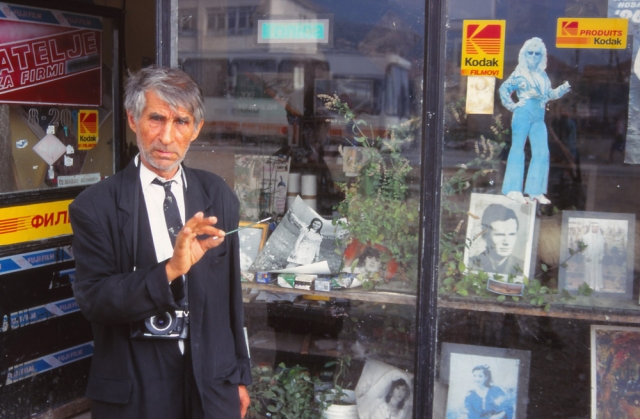

I didn’t have any particular interest in Yugoslavia at the time, probably because my expectations had been shaped by stereotypes of communist Eastern Europe. So I was greatly surprised to find, instead of a grey, homogenous land littered with dreary apartment blocks, a country of dizzying diversity.

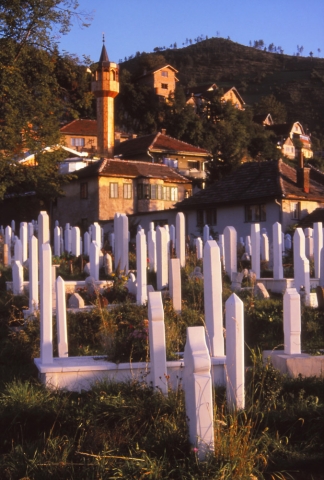

It was a country with half a dozen official languages where even the dominant language used two different alphabets, depending on which area you were in. Its people prayed variously in mosques, Catholic cathedrals and Orthodox churches, or were staunchly atheist Communists.

In the south, where the Turks held sway for centuries, I found towns where the food and minaret-studded skylines reminded me of the Middle East; in the north, the snow-capped mountains, haystacks and pastel-coloured churches could have come straight out of Austria.

Even the standard of living surprised me. I spoke to people whose basic needs were taken care of by the state but who also earned more than I could dream of without having to work very much at all. To cap it off, they lived in a country with a Mediterranean climate, a gorgeous coastline and decent wine.

[Story continues below the photo gallery]

I resolved to come back and explore Yugoslavia properly but, sadly, I was too late.

Even when I first visited in 1989 the wheels were starting to fall off. Josip Tito, the Partisan leader who led Europe’s only guerrilla war against the Nazis and later become Yugoslavia’s president for life, had died almost 10 years earlier. Without him the federation had started to fray. The very diversity which made the country so fascinating was about to blow it apart.

For a casual traveller like me, inflation was the most obvious sign that this union of south Slavic peoples (that’s what “Yugoslavia” means) was crumbling. It was so out of control I had to change money every morning because my wallet full of dinars lost value even during the course of a day. Shops put up a new price list very morning; cash was carried to the bank in bulging shopping bags. Later, in the early 1990s, Yugoslav hyperinflation hit a monthly rate of 313,000,000 per cent.

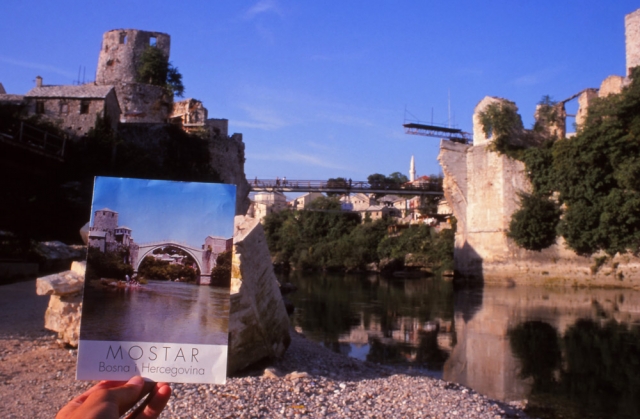

Though I never got to explore the old Yugoslavia I did return several times to its successor states. I travelled down Croatia’s stunning Dalmatian coast, went hiking in the mountains of Montenegro, visited land-locked Macedonia’s lakes and monasteries, was saddened by tragedy of Bosnia, and fell in love with Slovenia, a pocket-sized country with snow-capped mountains and a postcard-pretty capital.

The trip that left the greatest impression, however, was another accident. On that occasion a series of closed borders forced me to detour through Kosovo one month after the end of the Kosovo War. That trip will eventually get a blog post of its own.

These photos were taken between 1994 and 1999, after the independence of Slovenia and Croatia (1991), during the Bosnian War (1992-95) and just after the Kosovo War (1999). They are ordered geographically rather than chronologically, starting in Slovenia’s Julian Alps and ending at Lake Ohrid, where Macedonia meets Albania.

Like my other 1990s images, these are old 35mm slides digitised on a cheap flatbed scanner so the colours and sharpness aren’t quite right, but they offer a record of a fascinating and complex region nonetheless.