In a corner of a foreign field

Cabbage trees, flax and bush-clad hillsides plunging into a shimmering blue sea: Sounds like New Zealand, right? Well, not quite… This is the Republic of Georgia, and the sea in question is the Black Sea, not the Tasman.

For the few visitors who make it to this obscure corner of the former Soviet Union, the first hint that something botanically odd is going on comes at a Roman fortress just north of the Turkish border.

Its 18 black basalt towers and kilometres of walls enclose five hectares of lush gardens, where villagers tend kiwifruit vines and vegetable plots among the ruins.

But, for New Zealanders at least, having one of the world’s best-preserved examples of Roman military architecture to oneself is not the only surprise: Gonio Fortress is also crowded with cabbage trees.

Dozens of these unmistakeable New Zealand icons are scattered throughout the gardens. Others, the bases of their trunks whitewashed, form an avenue through the centre of the fortress; further on, two neat rows of flax lead to the grave of a Georgian saint.

After this unexpected find at Gonio, I started seeing New Zealand flora everywhere.

In the nearby city of Batumi I spotted a clump of flowering cabbage trees by the port, and many more surrounding a lake in a neglected park. A flax bush was thriving near Stalin’s one-time home, and what looked very much like a Dracophyllum was sheltering a group of old men playing backgammon outside a betting shop.

So what on earth is all this New Zealand flora doing in a country few New Zealanders have even heard of?

I found a clue a few days later at the Batumi Botanical Gardens, 10km north of the city at the aptly named Green Cape.

There, next to a bamboo picnic pavilion and a curiously spelt sign reading “Section of Neu-Zeiland”, a hillside thick with cabbage trees, flax and manuka drops steeply to a sandy bay.

It was a scene straight out of New Zealand – until a carload of holidaying Georgians pulled up in a modified Lada, Russian pop blaring from the stereo, to photograph each other in front of the exotic vegetation. They barely noticed the eucalypts across the road in the Australian section.

Later I tracked down Yuri Dzirkvadze, deputy rector of the Batumi Agrarian Institute, whose school occupies a corner of the botanical gardens.

After some linguistic difficulties, he told me – I think – that the gardens boast more than 2000 species of woody plant, 500 flowers and herbs, and one of the best collections of bamboo and camellia plants in Europe. There’s also a pretty good collection of rhododendrons.

The 114ha gardens are divided into three separate parks and nine phytogeographical sections, including East Asia, North America, Australia, the Mediterranean, the Himalayas and Transcaucasia.

At 1.2ha and with a mere 19 species, the New Zealand section is one of the smallest – but also one of the most interesting, Dzirkvadze said. For decades visitors had been helping themselves to cuttings from the cabbage trees and flax, which now grow as decorative plants all over Batumi.

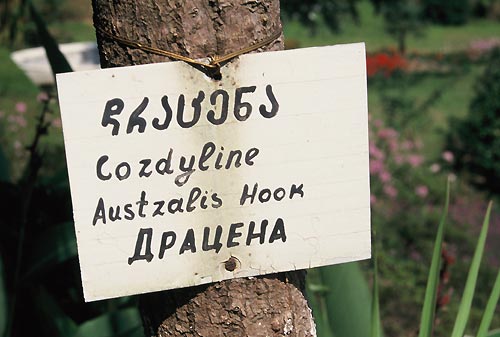

He then fished out a list of New Zealand species planted at the cape. And thank God for Latin: the Georgian language, with its unique alphabet and Byzantine grammar, makes even Russian seem straightforward.

Apart from flax, Phormium tenax, and the ubiquitous cabbage trees, Cordyline australis and Cordyline banksii, species in the New Zealand section include manuka, kowhai, leatherwood, broadleaf, rewarewa, lowland ribbonwood, a Hebe cultivar, a Pittosporum and two species of totara.

All very interesting, but I still didn’t understand how so much New Zealand flora ended up in Georgia in the first place.

I found the answer on Dzirkvadze’s bookshelf, in the form of the Concise Reference Book on the History of the Batumi Botanic Gardens. The book explains in charmingly idiosyncratic English how the gardens’ beginnings can be traced to the arrival of the Russian scientist Andrei Krasnov in 1893.

Impressed by Batumi’s mild climate and similarity to that of the Pacific – annual rainfall of 2600mm, average temperature in summer 22°C and in winter 8°C – he believed an exotic garden could help drag the region out of poverty.

“In spite of the neglected state of this area caused by unfortunate past, this site is magical with its southern climate,” he wrote, clearly relieved to have escaped the bitter winters at Kharkov University.

Krasnov’s goal was to create a “second motherland of subtropical cultures”, concentrating on rare and valuable plants from lands with similar soils and climatic conditions. In the process he hoped to make Georgia’s Black Sea coast as prosperous as the holiday resorts of Western Europe.

In 1895 he embarked on a year-long expedition to India, China and Japan, collecting flora on the way; in 1912 the Russian government granted 100,000 Roubles for the purchase of 72ha on Green Cape.

In the following year some 2000 species were planted on the cape, and Krasnov struck deals with botanical institutes across Europe, the US and Japan. The London Royal Botanical Gardens alone sent 300 species, including several from New Zealand.

An optimistic Krasnov said: “Less than 25 years will pass and this region will be better than the Riviera, people will walk along the alleys of evergreen oaks and palms and northern man will find the illusion of tropical countries here.”

When Krasnov died in 1914 he was buried in his beloved gardens, at the end of an alley of cypress trees overlooking the sea.

Somehow his gardens survived the Russian civil war, two world wars, and Georgia’s post-independence chaos and economic collapse. But, like the rest of the country, they have fallen on hard times.

Few trees are labelled and piles of rubbish moulder in the undergrowth. The Soviet-era cable car, which once carried crowds of picnickers up the cape, is now a jumble of rusting steel. Batumi’s biggest hotel, instead of accommodating tourists drawn to the city’s beaches and gardens, is home to hundreds of refugees from Georgia’s civil war with the breakaway province of Abkhazia.

So Krasnov’s dream of a prosperous Black Sea coast rivalling the French Riviera is as far from reality as ever – but the climate is still mild, the landscape magical, and the wine abundant.

The difference now is that, for the first time in a century, Georgia is open to western visitors. And some of those visitors will travel thousands of kilometres to find themselves gazing out over the sea and Krasnov’s cabbage trees, and wonder whether they had left home at all.

First published in New Zealand Geographic, July-August 2005.

Where in the world is Georgia?

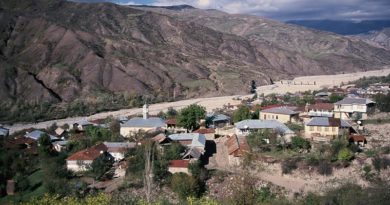

The Republic of Georgia is located at the eastern end of the Black Sea, sandwiched between Turkey, Russia and Azerbaijan.

It has an area of 70,000sq km, making it a quarter the size of New Zealand, and a population close to 5 million.

If anything, its geography is even more varied than New Zealand’s, boasting everything from a temperate coast with white sandy beaches to semi-desert, as well as snow-capped mountains more than 5000 metres high.

Its people speak Georgian, which has a unique 2500-year-old alphabet, and trace their ancestry back to Noah. It is one of the world’s oldest Christian countries, and its most famous – or infamous – son is Joseph Stalin.

The country gained independence from the Soviet Union in 1991 and plunged almost immediately into civil war. Once the most prosperous part of the USSR, state wages fell as low as US$5 a month in the nation’s post-independence chaos.

Unlike the Russians to the north, the Georgians drink wine, not spirits, and place great value on hospitality and honour.

Another link with New Zealand is the Georgians’ love of rugby with their national team regularly qualifying for the Rugby World Cup.