Peace at last for shipwreck’s ‘hungry ghosts’

The sinking of the SS Ventnor off Northland’s west coast in 1902 with 499 Chinese gold miners on board would have been New Zealand’s worst maritime tragedy — but for the fact that most of the passengers were already dead.

The ship was carrying the remains of men who had died in the South Island’s goldfields and were to have to been buried in their home villages in China.

According to traditional Chinese belief a soul can find rest only if its grave is tended by family members. In return for offerings of food and incense during the annual festival of Ching Ming, souls of the departed will grant the living a year of good luck and happiness. Lost or forgotten souls are doomed to wander the earth as “hungry ghosts”.

The loss of life when the Ventnor sank off Hokianga Heads was significant — 13 crew members drowned — but it was also a tragedy for the dead miners’ families. They were never able to bury their men or carry out the rites needed to put their souls to rest.

But that changed when, 111 years after the sinking, descendants of those pioneering miners were finally able to carry out the rituals needed to satisfy the hungry ghosts.

Just as importantly, the miners’ descendants came to Northland’s wild west coast to give thanks to the descendants of another people — the Māori of Te Roroa and Te Rarawa tribes who had found the mysterious caskets and bones on their beaches and buried them, sometimes alongside their own ancestors.

The final chapter of the Ventnor tragedy began with Rawene woman Wong Liu Shueng, a third-generation New Zealander whose roots lie in the same district as some of the lost miners.

She had long heard whispers about bones from the Ventnor washing up along the coast, so when she had to make a short film for a movie-making course in 2007 it was the obvious topic to tackle.

Ms Wong made contact with Te Roroa elders, who confirmed their ancestors had gathered the bones and buried them. Many were laid to rest in a wāhi tapu [sacred place] just south of Kawerua, on the edge of Waipoua Forest.

She also made contact with Te Rarawa further north, who had passed down similar stories, and began organising ceremonies to put the miners’ souls to rest and give thanks to west coast iwi. It was a slow, laborious process — but if the souls had gone hungry for more than century, she figured they could wait a few years longer.

The preparations were finally ready in April 2013, when 100 descendants of those long-lost Chinese miners — mostly from Auckland, but with a few from as far away as Hong Kong and Australia — travelled to Te Roroa’s headquarters in the Waipoua Forest to unveil a plaque amid a freshly planted kauri grove.

The inscription, in English, Chinese and Māori, reads: “With gratitude of the New Zealand descendants of the Poon Fah and Jeng Seng districts to the iwi [tribes] of this area for respecting and caring for the remains of the Chinese washed ashore following the sinking of the SS Ventnor on 28th October 1902. May their souls now rest in peace in your rohe [tribal area].”

They then travelled to Kawerua, the site of a once bustling coastal settlement, for the first of many bei jey ceremonies. The ritual honours the dead when the exact location of their remains is unknown and involves calling the ancestors, lighting joss sticks and sharing food, usually chicken and pork.

On April 5, 2013, the group made the long journey to Mitimiti, North Hokianga, where a century ago bones were gathered up and buried on the hilltop cemetery of Maunga Hione. The acclaimed Māori artist Ralph Hotere was laid to rest on the same hill earlier that year.

They were formally welcomed to Matihetihe Marae and dedicated another plaque, this one giving thanks to the people of Te Rarawa. It is mounted on what Ms Wong describes as a “spellbindingly beautiful” Chinese gate overlooking the sea.

The following day they visited the lookout at Signal Station Rd, from where the signal master watched the Ventnor slide beneath the waves, and the giant dunes of North Hokianga Head for a final bei jey ceremony.

Among the Chinese Kiwis in the group was Gisborne Mayor Meng Foon, who said he had joined the miners’ descendants because he wanted to be with them as they went “from grief to gladness”.

During yet another welcome, this time at Kohukohu’s Blackspace Gallery, Mr Foon said from the tragedy of the Ventnor had come diamonds.

“It was a tragedy for our ancestors who never got back to China. Their womenfolk, their children, are still mourning for them. But the beautiful thing about this is we’ve formed a new relationship with Te Rarawa and Te Roroa, and we’ve found strong similarities between the cultures — especially our desire to go home,” he said.

Te Roroa elder Alex Nathan said the story of the Ventnor’s bones was all but a myth to the Chinese community before Ms Wong made contact, so they were surprised to find it was common knowledge among Māori living on the coast.

The Chinese expressed their gratitude many times during the three-day visit but Māori did not bury the remains for the thanks, he said.

“Our people were just obligated to take care of the bones until such time as the rightful descendants appeared on the scene. They didn’t do it with a view to being thanked. It was an obligation, we’d do it for anyone.”

It was the first time many of the Chinese visitors had had such close interaction with Māori. They were surprised to discover parallels between the two cultures, and by the end were referring to their Māori hosts as “our long-lost cousins”, Mr Nathan said.

Thirty-nine of those taking part in the April 2013 journey were descendants of Choie Sew Hoy, an Otago businessman whose remains sank with the Ventnor. They included great-great-grandson Peter Sew Hoy, until recently a GP in Dunedin.

“To be the first descendants since the boat went down 111 years ago to be able to pay our respects and do the Ching Ming ceremony, at the site where Choie Sew Hoy is, was very, very emotional.”

Mr Sew Hoy hoped more descendants would come to the west coast each year to mark Ching Ming.

Ms Wong said on one level she was glad the journey she had begun many years to uncover the story behind the Ventnor’s washed-up bones, and give thanks to those who had cared for them, was now over.

Many of those who took part in the commemorations had discovered how much they had in common with Māori and some had even discovered family links. She was certain that all had gained a deeper understanding of what it meant to be Chinese.

And what about the hungry ghosts?

“I’m sure they’re smiling now. I’m sure they’re full up and I’m sure they’re happy.”

The Ventnor story

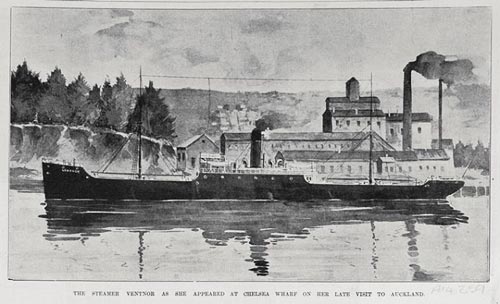

The ill-fated SS Ventnor was built in Glasgow in 1901 and chartered in 1902 by a charity called the Cheong Sing Tong, set up by the Chinese community in New Zealand to return the remains of their countrymen to their home villages in China.

In the 1800s thousands of Chinese men, mainly from the then impoverished province of Guangdong, came to New Zealand to dig for gold. Although life was hard they could earn a lot more in the goldfields than they could in China, and most hoped to return home to build better lives for the families they had left behind.

Many, however, died in New Zealand. According to traditional Chinese beliefs, graves must be tended by family members to ensure a good afterlife for the deceased and prosperity for their descendants — but that can only happen if they are buried close to family, usually in their home village.

Those who are buried where family members are unable to practice the proper rituals cannot rest in peace and become what is known as “hungry ghosts”.

Hence the efforts of the Cheong Sing Tong, which in 1883 collected the remains of 230 miners and shipped them home to China. In 1902 the society prepared an even bigger shipment, exhuming 499 miners from 40 cemeteries in Otago, Southland and the West Coast.

The bones were sealed in lead boxes, which where were then placed inside kauri caskets and taken to Wellington to be loaded into purpose-built compartments under the Ventnor’s deck. The ship’s other cargo was 5000 tonnes of West Coast coal destined for Hong Kong.

However, on October 27, a day after leaving Wellington, the ship hit a reef off the Taranaki coast. The captain decided to head around North Cape to Auckland for repairs but the damage was too severe. The ship sank off Hokianga Heads on October 28, taking its cargo and many of its crew to the bottom.

Figures for the death toll vary. It is thought at least 13 died, including the elderly Chinese “attendants” given free passage home in return for looking after the remains. An attempt by the Cheong Sing Tong to salvage the caskets failed.

The sinking was a great tragedy for the men’s relatives, who feared their souls would be unable to find peace.

Among those whose remains were on board was Cheong Sing Tong founding member Choie Sew Hoy, whose grief-stricken son Choie Kum Poy reportedly said: “My poor father, he has died twice”.

It is only in the past few years that the miners’ descendants have learned that not all 499 bodies sank forgotten to the bottom of the Tasman Sea. Some caskets washed up along the west coast from Kawerua in the south to Mitimiti in the north, where they were discovered by Māori of Te Roroa and Te Rarawa tribes and buried.

In Kawerua horses were used to drag the lead caskets up what later became known as Chinaman’s Hill; at Mitimiti, bones found scattered along the beach were gathered up and buried alongside Māori dead.

The story had been largely forgotten outside the west coast’s Māori communities until Rawene woman Wong Liu Shueng, whose ancestors hail from the same Jeng Seng district where some of the miners were born, made contact with Te Roroa for a short film about the Ventnor.

The April 2013 visit by the miners’ descendants was timed to coincide with Ching Ming, a festival dating back more than 2500 years in which people visit the graves of their ancestors, honouring them with incense and offerings of food. In return the ancestors grant their descendants a year of good luck and happiness. Translated as Ancestor’s Day or Tomb-sweeping Day, Ching Ming is a national holiday in China, Hong Kong and Taiwan.

The records of whose remains were on board have been lost so the only known descendants are those of Choie Sew Hoy.

He arrived in New Zealand in 1869, setting himself up as a merchant supplying the goldfields. His business acumen and command of English made him wealthy. He invented a dredge suitable for working river beds and eventually owned 11 mining companies. He founded the Cheong Sing Tong in 1882 and died in 1901.