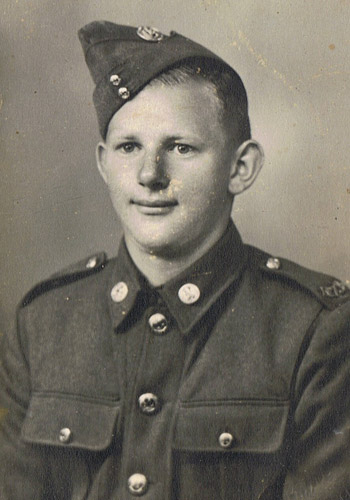

One man’s war: A Hokianga soldier remembers

Warning: This story contains graphic descriptions of war.

Bill Guest had a job to do before he went away to the war. It involved a bottle of beer, his local tavern, and a pledge of sorts to make it home alive.

‘‘Just before I left we had a few days’ leave, so I went up to Koke [Kohukohu] and went to the pub. I had a few beers then bought another bottle, gave it to the proprietor and said: ‘Stick that up on your mantelpiece, I’ll drink it when I come back.’ That bottle of beer stayed there for two and a half years, and it tasted bloody good.’’

Guest only left his beloved North Hokianga once, and reckons it was only good luck that he was able to reclaim that bottle — a Double Brown, probably — and tell his stories.

Not that he shared many of his tales when he first got back. Like many men of his generation, he filed his war experiences in a trunk in the attic of his lively mind.

Besides, life was busy with courting, raising children, and trying to scratch a living from Hokianga soil that was unforgiving and drought-prone even then.

Once grandchildren come along, however, it was different. Now 96, Guest relishes the chance to dust off his war stories. He’s even written a book, updated and republished just last year, called My Life Story: A Motukauri Soldier.

· · · · ·

Guest was raised at Pūrākau, a former mission station where the only access was by water.

If North Hokianga seems isolated today, in the 1920s the Guests might as well have lived on the moon. Family trips off the farm happened about three times a year; until young Bill was 8 his mum did her best to educate him at home.

Around 1930, along with his mum and younger brother Harry, he moved to a rough family bach in Rawene so he could go to school.

Later he walked kilometres through gorse each day to a newly opened school at Pūrākau; later still he moved in with his grandmother at Motukaraka so he could catch a boat to Rawene and go to high school.

‘‘That was until the teacher told me I was dumbest joker he’d ever tried to teach, so I left school and worked on the farm. I was 13 years old.’’

· · · · ·

Guest was 18 when Nazi Germany invaded Poland. Within days Britain and France had declared war. World War II, a conflict which would draw in 140,000 New Zealanders and claim the lives of 12,000, had begun.

‘‘I tried to join the army straight away,’’ Guest said.

‘‘I went over to Rawene to see the doctor and sign up, but he said my blood pressure was too low so I couldn’t pass. He saw I wanted to join the army so he said, ‘Run down to the end of the wharf and back up here as quick as you can, then I’ll take your blood pressure again.’ That’s how I got in.’’

Guest spent two years camped near Ōkaihau with the Territorials, then another six months in Whangārei.

When he turned 21 he was finally sent to Egypt and from there to Italy, where Allied forces were pushing the Germans north.

Usually new arrivals had a few weeks in Bari, a port city, to get vaccinated and prepare for battle. But not Guest. After years of training and marching from camp to camp around Northland, when his war started it did so suddenly and brutally.

‘‘The 12th Reinforcements had a lot of casualties and they were under-strength, so they sent me and two other jokers up to join them. I’d only been two days at base camp.’’

‘‘I got there at midday and that evening they were planning a big attack on the Pisciatello River (in northeastern Italy). We were just waiting for dark when a shell came over and exploded and killed one of our jokers. It cut another joker’s throat and I had to watch him just bleed to death, I couldn’t do anything.’’

That soldier was the platoon’s Bren machine gunner, an important but dangerous role.

‘‘I had to take his gun over and be the Bren gunner. I couldn’t give that away to anybody during the whole of the war, nobody wanted it because whenever you approached the Germans, the joker with the Bren gun was the first one they’d shoot at.’’

Even Guest isn’t quite sure how he survived.

‘‘Just very good luck, I suppose.”

· · · · ·

Nor were German marksmen the only danger. One of Guest’s strongest memories involved nearly drowning in a cesspit full of sewage.

On the eve of a battle for the town of Faenza, south of Bologna, Guest developed a severe case of jaundice.

However, his platoon was so depleted — it had just 17 men instead of 30, and half of those had never seen action — he wasn’t allowed to seek medical help until the battle was over.

Most fighting took place under cover of darkness but on this occasion his platoon was ordered to a launch a daylight attack on a house full of Germans to strengthen the line before the night-time offensive.

“So another joker went up and threw grenades through the window, and seven Germans came out and surrendered. The commander told our corporal to check around the back of the house. There was a great explosion and two men came back but the corporal didn’t.”

Guest was sent around the back of the farmhouse, alone, to find out what had happened to the corporal. But the moment he rounded the corner a German stepped out from behind a haystack.

“As his arm went up to throw a grenade at me I shot him. He was lying on the ground making a hell of a bloody noise — and then I fell in a cesspit.”

In those days every Italian farmhouse had a deep concrete pit outside the back door. Any time the stables were swept out all the straw and animal excrement went into the pit, along with human waste from the house. Once a year the muck was shovelled out and spread on the fields.

“It’s not nice, and when I fell in my head and everything went under. I was stuck and couldn’t get out.”

When Guest also failed to return, a mate, Bill Curry, volunteered to look for him. There could have been any number of Germans still waiting around the back of the house, making it an act “ten times braver” than that which earned Willie Apiata the Victoria Cross.

Once Curry had managed to pull his mate out of the pit they went looking for the corporal. They found him with his stomach blown open by a grenade.

“Then he went up to German who was still lying on the ground moaning and groaning, and said to him, ‘You killed my best mate, you bastard’, put his gun on his forehead and pulled the trigger. One of the jokers in our platoon was very religious and made a hell of a stink about it.”

· · · · ·

Guest himself lost any religious convictions he had some days earlier when his platoon was helping dig through the remains of a church hit by German bombs.

Several young priests were busy retrieving altar candles dug up by the Kiwi soldiers but wouldn’t even look when they found a young girl under the rubble. To teach the priests a lesson the soldiers stole the candles, which in the army were strictly rationed and used only for map reading, then returned to their digs.

“We were playing cards until midnight for ages with those giant candles,” he said.

· · · · ·

The rest of the attack on Faenza was uneventful and the following morning the jaundiced Guest was sent back to the nearest medical post, a walk of about 8km.

On the way he passed the house where he had fallen into the cesspit and wrapped the dead corporal in his gas cape, to give him some kind of dignity until he could be buried.

“When I rolled him over to get the cape around him all his guts fell out and I had to put them back in … I was thinking how much they looked like a sheep’s,” the Hokianga farmer said.

When he arrived at the first aid post he saw a row of soldiers laid out on the ground and wrapped in blankets.

Among them was Alf Harrison, from Utakura, Guest’s best mate and the only other member of the 24th Battalion from North Hokianga.

“That’s how I found out Alf was dead. That was very, very upsetting.”

· · · · ·

Guest was put on a hospital ship and sent back to Bari. Once he was cured, about two weeks later, hospital orderlies handed him back his uniform.

They had folded it carefully but it was still wet and stank of excrement from the cesspit.

“I kicked up a hell of a stink, so they kept me in hospital another day until they got me a new uniform.”

While he was waiting at army headquarters for a ship back up the coast, he was ordered to report to the adjutant.

“I thought, What the hell have I done wrong now? But when I got there, it turned out he’d been a second lieutenant when I was in the Territorials in Ōkaihau. I used to spend a lot of time at night playing cards with him.”

The adjutant told Guest he’d seen his name on a list and asked him what his plans were.

“I said, ‘Go back to the 24th, I suppose’. But he said, ‘You’ve done your duty. You stop here with me, I’ll give you a job here at HQ, make you a corporal and later make you a sergeant’.”

“I thought hard about it and thought about all my cobbers in my platoon … I had to go back to them. He told me I was a proper bloody fool.”

When he got back to his platoon he found several of his mates had been killed while he was in hospital and the commander had suffered a breakdown. His replacement was a “no-hoper” who’d served in the Pacific but never been within 100 miles of a Japanese soldier. Most of the men were new recruits.

Did he ever regret turning down the adjutant’s offer?

“Very much so,” he said.

· · · · ·

One of Guest’s most frightening experiences came during an attack at the Senio River.

The New Zealanders were dug in on one side of the riverbank and the Germans on the other; for days they threw grenades back and forth at each other. The grenades had a four-second pin, meaning they exploded four seconds after the pin was pulled.

Guest was sharing a foxhole with a new recruit who would wait two seconds before throwing each grenade, so it exploded in mid-air and spread shrapnel over a larger area.

“But his two seconds got longer and longer and I was scared to bloody hell he was going to blow both of us up. He said he wasn’t that mad but about half an hour later he held one too long and blew his hand off. So that was the end of the war for him. He’d been in Italy less than a month. That was very frightening.”

· · · · ·

Germany’s surrender in May 1945 heralded a golden time for the young soldier. The fighting was over but there weren’t enough ships to take the troops home. For Guest, that meant another nine months in Italy, sometimes staying in army camps but other times in fine hotels.

The Kiwis of the 24th Battalion were the first troops in Trieste, northern Italy, after Tito’s Yugoslav partisans pulled back to their side of the border. That meant they had first dibs on the city’s finest waterfront hotel and swam in the Adriatic every day.

Next he was sent to Genoa, a staging post for returning British troops, where Guest’s job was to ensure they were suitably equipped with tobacco and condoms for the journey home.

Most of the departing soldiers opted to save their money rather than buy condoms but army command kept sending up bulk supplies. There was little to do but dispose of the surplus on the black market, where tobacco sold for 500 lire and condoms — contraband in staunchly Catholic Italy — for 1000 lire a packet of five.

“That was a hell of a lot of money and we had a glorious time. We never cooked, we went to Italian restaurants. There’d be girls there and if you shouted them dinner some jokers would take them home for the night, though my cobber Ivan Whyle wouldn’t let me.”

Guest also spent some time camped near Venice, seizing the chance to visit Florence and Pisa. On another occasion he was issued a pass to travel to the Alps but went to Monte Carlo instead.

“It was full of Americans, they gave us free tucker and petrol. We had a great trip,” he said.

· · · · ·

Coming home wasn’t easy. Guest returned during the worst drought in decades with cattle like bags of bones and drinking water shipped over from Rawene in cream cans.

Some of his army mates made up tales about their farm experience, were granted soldier’s rehabilitation loans, put sharemilkers on their newly bought farms and spent every evening at the RSA.

When Guest applied, however, the loan scheme’s pen-pushers dismissed his farming experience in North Hokianga.

“They told me to get off down to Waikato, get a job there for 18 months and learn to be a farmer, then come back again for a loan. I was hot-headed in my younger years so I told them I’d spent three years fighting for bastards like them and I’d go to the bank and borrow off them instead.”

· · · · ·

These days Guest still lives on the farm at Motukauri, in a house he built himself by felling macrocarpas his grandmother had planted and making 800 concrete blocks with local sand and shingle.

Earning a living from the land in North Hokianga still isn’t easy — the bees, which Guest has kept since he caught his first wild swarm as a boy, make more money than the rest of the stock put together — but the view straight down the harbour as far as Ōmapere and the North Hokianga dunes is still magical.

Guest’s wife, Nan, and siblings have passed on, but many of his children, grandchildren and his first great-grandchild live just over the hill. Thanks to Nan Māori blood flows in all his descendants’ veins, just as he wanted.

Guest’s knees are shot and his mobility is reduced but his mind is still strong, always looking for new projects and challenges. He’s still deeply attached to the land he left just once, then returned to more than 70 years ago to reclaim a bottle of beer from his local’s mantelpiece.

“I’m not going anywhere else. When it’s time I’m going under one of those kauri trees I’ve planted. There’s already three of us down there, and my sister’s in a box in my bedroom. One of these days she’s coming with me.”

First published in the Northern Advocate, April 2019.

Wonderful story. My parents told us about the local boys of the Hokianga who learned to fly and how they would come and fly over the playing fields of the school.

Thanks Patricia! Glad you enjoyed the story about Bill. He’s a great Hokianga character.