The life of Brian

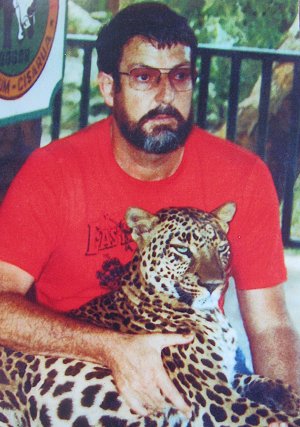

A former television reporter, uranium prospector and English teacher to Bangkok prostitutes. A man who has cheated death, notably when a supply drop went horribly wrong and his host — a New Guinean tribesman — was crushed under a 50kg bag of rice. A man who flits from scholarly eloquence to four-lettered crudeness. A man who is anything but your average natural scientist.

When asked how many species he has discovered, Brian Parkinson waves a hand and mutters self-effacingly, “about 30 or 40”.

Seven of those are named after him, including Oliva parkinsoni, a carnivorous seashell of the Indian Ocean; Megalacron parkinsoni, a tree-dwelling snail of New Guinea; and Melanotaenia parkinsoni, also known as Parkinson’s rainbow fish. (Now popular in aquariums, Parkinson discovered it in a creek behind a New Guinea airport while waiting for a flight.)

But for the last decade, Parkinson has forsaken the creeks and reefs of the tropics and devoted himself fulltime to writing. The publication of two new books — Butterflies and Moths of New Zealand and Field Guide to New Zealand Seabirds — confirms his reputation as one of the country’s most prolific nature writers, with more than 20 books published to date.

It’s not a bad achievement for a country lad who left school at fifth form and started his working life artificially inseminating cows.

· · · · ·

The strength of the Field Guide to New Zealand Seabirds, according to Southland Museum ornithologist Lloyd Esler, is that it covers absolutely everything.

“It’s got every seabird that’s ever shown its beak in New Zealand, and that’s what makes it so useful,” he says.

More than 100 species are listed, from the common and garden black-backed gull to the oddly named masked booby and the Chatham Island taiko, probably the world’s rarest seabird.

Once the taiko must have lived in huge numbers on the Chatham Islands, says Parkinson, but when humans and rats arrived its population rapidly declined. It was presumed extinct for almost a century, until one was found off the Chathams in 1979.

The taiko is still so scarce the only photograph that could be found shows a rather unhappy specimen perched on a table, surrounded by coffee cups. The photo had to be cropped for publication, as it was felt the cups did not accurately reflect the taiko’s natural habitat.

· · · · ·

New Zealand is one of the world’s great seabird centres: Three-quarters of the world’s albatross, penguin and petrel species are found here.

“It’s also the shag capital of the world — we have 13 or14 species, half of all the shag species in the world,” says Parkinson. Australia, by comparison, has a mere three.

This great diversity came about thanks to New Zealand’s many offshore islands, and — until the arrival of humans — the lack of mammalian predators, which allowed seabirds to nest as far as 100km inland.

“The Field Guide to New Zealand Seabirds is a book everyone should buy,” he says.

“All New Zealanders should have an understanding of the unique wildlife that surrounds us…”

Parkinson glares at the reporter’s notebook, tugs at an unkempt silver beard, and scowls.

“You’re not writing that namby-pamby crap are you? What should I care if anyone buys it?” he says.

It’s hard to know when Parkinson is pulling your leg, and when he’s deadly serious. Even his least pleasant memories are delivered as barbed jokes or self-deprecating anecdotes.

· · · · ·

But not everyone gets the jokes. Parkinson recalls an amusing evening almost 40 years ago when he was invited to speak at a meeting of the Forest and Bird Society. He has not been invited since.

“A friend and I decided to talk about an expedition to the Caribbean and the fascinating wildlife we’d seen, such as the rosy-bottomed pushover, the gimlet-eyed titwatcher, the furtive nutscratcher and the lesser woolly pervert. Of course we’d never been anywhere near the Caribbean and the account was entirely fictitious,” says Parkinson.

Parkinson’s workplace is a modest home he shares with his sister Robyn in the Auckland suburb of Mt Roskill, a household where scholarship takes precedence over dusting. Shelves sag under the weight of books; carved masks stare from the walls; a giant fossilised crab battles for space on the mantelpiece with a bronze Buddha and a Tibetan monk’s leg bone.

Parkinson, clad in jeans and a T-shirt of indeterminate colour, runs a hand through tangled black hair and the story begins. This is the life of Brian.

Born in Opotiki in the eastern Bay of Plenty in 1944, Parkinson was the middle child of three. His father was a farmer and stock dealer; his mother the town’s librarian and keeper of morals.

“She didn’t let anyone order any dirty books. You had to ask for anything you wanted at the desk in a loud, clear voice,” he says.

His sister Robyn remembers his kindness to animals, how he would sometimes appear at her convent school cradling a hedgehog rescued from the road. Parkinson credits his grandfather, a man who dedicated himself to caring for ailing penguins and rescuing kiwis from gin traps, with his love for nature.

The young Parkinson and his sisters were the only Catholic children in the district, at a time when religious animosity still ran deep:

Catholic dogs, sitting on logs,

Eating bellies out of frogs.

At the age of 12, loyal to family tradition, he was sent to Sacred Heart College, a Catholic boarding school in Auckland. It was not an experience he would recommend to anyone.

“It made you terribly pessimistic about human nature — and in those days physical abuse was just part of the curriculum,” he says.

· · · · ·

When Parkinson finished fifth form, he returned to Opotiki to help run the family farm. His father’s drowning two weeks later changed all that.

After drifting from farm to farm as a herd tester and artificial breeding technician, he joined the Wildlife Branch (now the Department of Conservation) and dropped out of Victoria University in his third year. In 1965 he became NZBC science reporter for the television station AKTV2.

Parkinson left New Zealand at the age of 23, the beginning of two decades of travel that would take him to more than 100 countries — his passport is thicker than some provincial telephone directories.

He started out in Australia as an opal miner and landscape gardener in Alice Springs, which, given the climate, involved little more than shifting cacti around. That was followed by a “very un-PC” job prospecting for uranium by plane.

“We’d fly about 300 feet above the ground, and my job was to take radiation readings. When the readings shot up I’d have to try and work out where we were on the map.”

Fortunately, says Parkinson, his map-reading skills at the time were such that he doubts any of the uranium deposits were ever found. His days as a uranium hunter were finally brought to an end by an evening’s overindulgence in the local brew.

“I’d had a hard night, we were flying at 200 feet, going up and down, and I felt rather queasy. The pilot said we’d land for a while in a dry riverbed we could see just ahead, and that it’d be a ‘piece of piss’ — but even in my delicate condition I could see it wasn’t a suitable landing ground.”

Those misgivings proved well founded when the plane hit an unseen watercourse, flipped several times and burnt out.

“And after all that I didn’t even throw up,” says Parkinson.

· · · · ·

Forced to seek alternative employment, Parkinson took a job prospecting for minerals in what was then the Territory of Papua and New Guinea, where he spent much of the next 15 years.

“Working in those remote areas really cultivated my interest in nature — it was so fascinatingly untouched and primeval,” he says.

At that time much of the island was still a restricted area, and many of its tribesmen had never seen a European. The prospectors were to be accompanied by a patrol officer and six policemen at all times, but Parkinson’s never showed up. Despite that, he says, he only ever got into “one or two minor scrapes”.Parkinson’s supplies were dropped in by air, and he instructed the villagers never to catch anything falling from a plane.

“Unfortunately, the local headman did try to catch a 50kg bag of rice dropped from 1000 feet. I thought they were going to kill me.”

Luckily for Parkinson, the deceased’s relatives accepted the apologies and the gifts of axes and bush knives. He survived, only to get himself into a worse spot while prospecting in the Star Mountains, near the border between New Guinea and what is now called West Papua.

“We were collecting stream sediment samples at about 8000 feet, and we had to climb up a bank to negotiate a narrow gorge. The path gave way and I fell back into the river, managing to break my arm and three vertebrae.”

“I lay there for 20 minutes, because all my merry men had buggered off. When I saw one poke his head around a tree I sconed him on the head with a rock, to show him I was still alive and nasty.”

He recalls his fear during the long trek to a patrol post that his stretcher bearers — clad only in traditional penis sheaths — would drop him and that he would poke an eye out on their fiercely pointed attire. Those fears were not realised, but all the same his prospecting days were ‘bugar-up finis’, as they say in Pidgin.

· · · · ·

In 1974 Parkinson was approached by the government of newly independent Papua New Guinea to direct a nationwide marine survey. The plan was to train a team of divers and study whether the country’s shellfish and coral resources could be harvested.

It was then that he penned his Pidgin classic, Wok Bisnis bilong salim Sel, literally ‘work business belongs selling seashells’, a guidebook explaining how to make money selling shells to Western collectors.

The epic Tropical Landshells of the World also dates from that period, a book hailed by the British Museum of Natural History as “one of the great works of malacology” and “a glorious addition to the literature of conchology”. To the uninitiated, that means it’s a bloody good book about snails. It was written while the author was living in Bangkok and paying the bills by teaching English to “ladies of negotiable virtue”.

Other marine surveys followed in Tuvalu, the Seychelles and finally Fiji, funded by the UN and the South Pacific Commission, until the 1987 coup forced him to return to New Zealand.

Now he has devoted himself to helping New Zealanders understand this country’s extraordinary flora and fauna.

“People need to be educated how to treat wildlife, to give it the respect it deserves.”

Parkinson’s rules are simple. Keep away from birds; don’t come between birds and their nests, or between marine mammals and the sea; don’t stay around if the animal becomes agitated; and, above all, don’t touch.

“It’s a bit annoying when a penguin comes out of the surf and someone pops up in front of it from the dunes — the penguin goes back to the sea for the rest of the day, and the chicks don’t get fed.”

Parkinson has even seen tourists at Cannibal Bay in the Catlins sitting on sea lions to have their photo taken.

“I used to stop them, but now I prefer to leave it to natural selection,” he says.

· · · · ·

Habitat loss is another threat to New Zealand’s sea and shore birds. The Firth of Thames is a popular destination for the godwit, a protected bird that flies 15,000km from Siberia every summer. The birds return to the same area generation after generation, even now that one of their favourite spots on the Thames foreshore is occupied by a shopping centre.

“They’re creatures of habit — you can’t get them to start taking their holidays in Whitianga just because someone’s built a shopping mall on their traditional roosting ground. Therefore it would be a spirited gesture by the people of Thames to have the mall razed by next summer,” says Parkinson, only half jokingly.

Similarly, thousands of pied oystercatchers and a few rare wrybills (so named because they are the only birds whose bill bends to one side) make their winter home at a railway marshalling yard in Otahuhu, in the industrial wasteland of South Auckland.

“Normally they’d be at the shore, but there they’re disturbed by people walking their dogs, by uncontrolled dogs, cats and weasels. They’re safer on the rail depot roof.”

Parkinson’s current project is a book on alpine flora and fauna, which involves many a trip to New Zealand’s high places seeking out camera-shy insects and diminutive flowers.

He claims, typically tongue-in-cheek, that he is sick of climbing mountains at 4am to listen to the dawn chorus, and hopes his next book will be about species that live in hotel carparks close to good restaurants.

Otherwise, Parkinson is vague about his future plans: “I’m still deciding on my career, though I must say my options are getting fewer.”

First published in the New Zealand Listener, March 2001. Main image by Cuni de Graaf.

Hi Brian,

I went through old bookmarks and found 2 of your addresses.

This may be better way to communicate, if this still works.

Ciao, Peter

Ahoj Petře!

I’ll pass your message on to Brian, who will celebrate his 80th birthday shortly.

Peter de Graaf