On an Italian mountain high

Hiking in New Zealand requires a certain amount of sacrifice. Any self-respecting Kiwi hiker expects to endure — even enjoy — day after day of sandflies, rain and dehydrated meals tasting of boiled foam rubber.

Not so in Italy. As my companion and I tucked into a plate of gnocchi washed down with a few glasses of wine on a cliff-top balcony high in the Dolomites, we decided it was a style of hiking that would be very easy to get used to.

The limestone Dolomites, in the north-eastern corner of Italy, are quite different to the granite, glacier-sculpted Alps to the north. Erosion has carved the white rock into gravity-defying towers and pinnacles that soar above picture-postcard meadows dotted with cows, their brass bells tinkling. Even without good food and coffee, it’d be a fine place for a hike.

We stumbled off our overnight bus in Bolzano, transport hub, capital of the Trentino-Alto Aldige region and gateway to the Dolomites. The city also suffers from a kind of cultural schizophrenia. Alto Aldige, alias South Tyrol, was part of Austria until the end of World War I and still has a strong German flavour. This would be of limited interest to the tramper except for one important thing — it means that every town, mountain and minor geographical feature has two names, one Italian and one German.

Despite the confusion resulting from an Italian map and a German bus timetable, my companion, Timothy, and I eventually made it to the trailhead, the 2100m Passo Falzarego.

From the pass, serious hikers scramble 600m up a crumbling limestone bluff. We decided to take the cable car. We were directed to a side window where we were handed a crash helmet and a set of protective leather clothing each.

“What kind of cable car is this?” we asked in horror.

It turned out to be a case of mistaken identity — we looked “identisch” to a pair of motorcyclists who’d left their gear behind for safekeeping.

The cable car deposited us a short stroll away from Rifugio Lagazuoi (2750m), a hikers’ hut atop a precipice with sublime views of the mountains. But hut is perhaps not the right word. Called a rifugio in Italian or Hütte in German, our accommodation — family owned and run with pride — had more in common with a luxury chalet than a refuge or a hut.

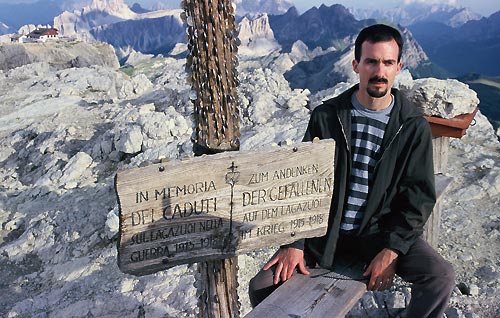

After dinner and a shot of espresso of near-lethal strength, we set off to explore. On a nearby peak we found a life-size crucifix commemorating the dead of World War I.

It seems improbable, but the Dolomites were the scene of heavy fighting between the Italian and Austrian armies in 1916. Some of the mountains are like Swiss cheeses, riddled with tunnels carved by half-frozen soldiers using little more than teaspoons.

The memorial left us reeling with culture shock: Hundreds of coins were wedged into the cracks of the cross, and a cake tin nearby was stuffed with banknotes. Why hadn’t anyone nicked it all?

Our plan the next day was to follow part of Alta Via 1, one of six long-distance routes that traverse the mountains. I had come prepared with enough equipment for two weeks in southern New Zealand in midwinter. Timothy, on the other hand, had a daypack containing a toothbrush and a sleeping bag. It soon became clear that Timothy had done a better job of anticipating the conditions.

At first we found the Alta Via disappointing. Apart from one steep climb up scree and teetering rock to a pass, the trail was wide enough to drive on and crowded with loud, obnoxious day-trippers. We soon learned the best tramping lay off the main route on the higher, less frequented trails.

One such detour took us across the Fanes Plateau, a textbook karst landscape of sinkholes and delicately sculpted limestone formations. We spent all of one stormy afternoon exploring and arrived at the next hut soaked, exhausted and ecstatic. The Italians huddled inside thought we were barking mad.

Further on, Alta Via 1 ranged from the hellish — where the trail met a road, with all the resulting crowds and commerce — to the eerily beautiful. It took in deserted plateaux speckled with edelweiss and rusting World War I debris, clusters of weathered timber houses where butter-makers once passed the summer months, and lots of cows with bells on.

One night we stayed in a hut run by the Club Alpino Italiano, Refugio Biella. Simpler and cheaper than the family-owned chalets, the club huts cater to the more serious hikers. They also give a 50 per cent discount to members of any hiking club. Fortunately, Timothy happened to have a monthly pass from the Prague Public Transport Authority which had a logo that could just about pass for a row of mountains. We were welcomed into the international brotherhood of mountaineers and got a cheap night’s sleep.

But the Dolomites were saving the best for last. As we were climbing to a final saddle, the 2330m Forcessa di Cocodain, we almost tripped over a herd of ibex.

If you haven’t seen an ibex, imagine a mountain goat on steroids with huge curving horns. We counted 17 of the beasts, sitting on the track, chewing their cud and taking in the view. Occasionally they had a go at head-butting a sign welcoming visitors to Parco Naturale delle Dolomiti. They certainly weren’t interested in us.

One of the difficulties we had in the Dolomites is that we never knew how to greet people.

If we wished someone a “buongiorno!”, they’d bark back at us in German; if we tried German they’d shrug and reply in Italian. We decided it was safer to try English first.

Eventually we established that Refugio Vallandro, a classic Alpine chalet and our last night’s accommodation, was German-speaking. Noting our interest in the local schnapps, and no doubt pleased to have some fools spending up at the bar, the owners poured us a few glasses of their home-made firewater.

“Fantastic! We’ll take the whole bottle,” shouted Timothy, once we’d regained consciousness. The barman laughed and showed us a three-litre flagon.

It was a fine night and a fitting end to our hike. Plus our hangovers helped to dull the shock of returning to the other Italy the following morning — the Italy of traffic jams, overpriced designer shops and homicidal young men on motor scooters.

Italy may not have much in the way of untouched wilderness, but if you like to end a day of serious walking with fine food and a good espresso, the Dolomites are hard to beat. Our only regret was that it would be hard going back to dehydrated mince and instant coffee.

Hiking the Dolomites

Bolzano, gateway to the Dolomite Mountains, is well served by trains from northern Italian cities. The same can’t always be said for transport to the trail heads.

For information on Servizi Autobus Dolomiti bus routes see www.sii.bz.it — the site has an English version and will find the best connection by train, bus and even cable car — or ask at Bolzano’s tourist office, on the main square about 200m from the railway station.

Be sure to bring a map. Topographic maps published by Kompass or Tabacco are sold in outdoor equipment stores around Europe. The 1:25,000 scale maps are best, but 1:50,000 is sufficient.

If you’re unsure where to go, you could base your hike around the long-distance trails that traverse the Dolomites. Each of the six Alta Via is clearly marked with colour-coded signposts and symbols painted on the rocks.

It’s a good idea to book your accommodation a few days ahead, but you will always get a place to sleep in an emergency. The privately-owned hikers’ chalets, called rifugio in Italian or Hütte in German, provide meals and a choice between rooms and dormitories. Most have a bar and all make excellent coffee; food is more expensive than in the cities, but it beats lugging your supplies across the mountains.

The Alpine Club-owned huts are cheaper and more basic. If you belong to a hiking club anywhere in the world, be sure to bring proof of membership because it may get you the discount. A New Zealand Federated Mountain Clubs card, for example, is just the ticket. Note that club hut accommodation is dorm only and you will need a sleeping bag. And possibly ear plugs.

If you have some spare time in Bolzano, it’s worth visiting the city’s most famous resident — although he’s been dead for 5000 years. Ötzi the Iceman, discovered in a glacier high in the mountains in 1991, is the oldest frozen mummy ever found. He now resides in a freezer in the Museo Archeologico dell’Alto Adige.