Hundertwasser in Holland: ‘Your loss is our gain’

For more than 20 years controversy has raged around a building in Whangārei in northern New Zealand.

Designed by the eccentric Austrian-born artist Friedensreich Hundertwasser, the waterfront building — if it ever gets off the ground — will feature a grass roof, a golden onion dome, curves in place of straight lines, and a patchwork of brightly-coloured tiles.

The on-again, off-again project has been making headlines since it was first mooted in 1993. It’s still a polarising issue, sparking countless letters to the editor, well-organised campaigns for and against, and even a public referendum won by the pro-Hundertwasser camp.

You’d be hard pressed to find anyone in Northland who hasn’t heard of the Hundertwasser proposal, or a Whangārei resident who doesn’t have a strong view on the issue.

However, few people know Hundertwasser also designed a building for Wellington as a tribute to his adopted homeland — he lived near the northern town of Kawakawa from the 1970s until his death in 2000 — and that the building he dubbed the New Zealand Spiral Monument was eventually built in the Netherlands instead.

Renamed the Rainbow Spiral, Hundertwasser’s only building in the Netherlands is the centrepiece of a holiday complex for families with disabled children called Kindervallei (“Children’s Valley”).

The brightly coloured building, with Hundertwasser’s trademark grass roof, onion dome, irregular tiles and abhorrence of straight lines, has become a tourist attraction in Valkenburg, a small town in the south of the Netherlands.

Locals, such as Kindervallei guide Ingrid van der Pal, don’t understand why the Spiral Monument wasn’t built in New Zealand but they’re delighted it ended up in Valkenburg instead.

So how did a building intended as a tribute to a bicultural Aotearoa end up on the other side of the world?

The saga began in 1987 when Hundertwasser designed what he called a “Māori house pā and national monument” for the Wellington waterfront, near the site now occupied by Te Papa, the national museum.

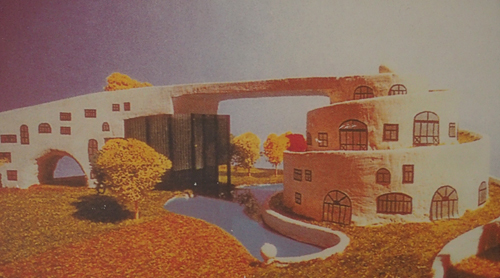

It was supposed to be five storeys high with a spiral-shaped Māori pā connected to a sloping “European pillow” by a grass-covered bridge. He wanted it to house museums documenting Māori and settler history, a library, conference hall, cinema and restaurant.

He said the monument would “lift New Zealand up to a nation with a high culture and high standard of humanity, giving the world an example of how to act as a bicultured [sic] society and to act in harmony with the laws of nature and human creativity”.

Hundertwasser, however, refused to enter his design in an architecture competition — in part, according to the Vienna-based Hundertwasser Foundation, because he believed he was the subject of “intense animosity” from other architects.

A model made for the Wellington City Council was displayed in the mayor’s office but disappeared a few years later. Its current whereabouts are unknown.

That would have been the end of the New Zealand Monument but for a Dutch charitable trust organising summer camping holidays in Valkenburg for families with disabled children. The trust was keen to offer holidays year-round but its teepee-style tents offered little protection from the Dutch winter, so its supporters went in search of a suitable building.

In Essen, across the border in Germany, they visited a Hundertwasser-designed Ronald McDonald House offering accommodation to families with children undergoing hospital treatment, and decided it was exactly what they wanted.

Ms van der Pal said Kindervallei’s trustees contacted the Hundertwasser Foundation in Vienna and were told the artist’s designs could not be copied or built more than once. However, the foundation just happened to have a “spare” design which had never been built — the New Zealand Spiral Monument.

Austrian architect Heinz Springmann, who also drew up the plans for Whangārei’s Hundertwasser Arts Centre, turned the artist’s rough sketches into a formal design. Construction of the Rainbow Spiral took 18 months and cost 6.2 million euros (NZ$10.6m).

With no government funding the trust had to rely on grants and donations of cash and materials. The colourful, two-part building was opened in 2007.

The spiral part, based on the shape of a Māori pā, houses offices and six Ronald McDonald rooms for families of children being treated in nearby hospitals or rehabilitation centres.

The other half of the building, called Ypsilon (Greek for the letter Y) because of its shape, contains eight holiday apartments for families with disabled children. Ypsilon also has a theatre, communal kitchen, dining area, library and a “snoezelkamer”, a sensory stimulation room for children with intellectual disabilities.

The apartments feature the kind of quirky details familiar to anyone who has spent a penny at the Austrian artist’s famous toilets in Kawakawa. Trees sprout inside the building, the irregular floors mimic ponds, and no two cupboard door handles are alike. Outside, a wheelchair-accessible treehouse is based on Hundertwasser’s beloved boat, Regentag.

The building’s design had to be tweaked to suit its new purpose — by making the roof garden negotiable to wheelchair users, for example — and every change had to be approved by the Hundertwasser Foundation.

Ms van der Pal said the cost of staying at Kindervallei was kept as low as possible, 15 euros a night per apartment, because price could not be a barrier to any family that wanted to stay. Eighty volunteers took care of everything from gardening to guiding visitors and doing the laundry.

The trust wanted to see the building utilised as much as possible with recent uses including a week-long camp teaching teens how to live with type-1 diabetes, a medical symposium and a children’s chess championship.

New Zealand’s loss was the Netherlands’ gain, she said.

“Your miss is our luck. It wouldn’t have been here otherwise. It was meant to unite people, Māori and Pākehā. It symbolised the coming together of two peoples, united by a bridge. Here, we say it unites disabled children and able-bodied children.”

Ronald McDonald Kindervallei is located in Valkenburg aan de Geul, in Limburg province, about 220km south of Amsterdam. Guided tours are held on Tuesdays, Wednesdays, Thursdays and Saturdays for 11 euros (NZ$19) per person.

Update: After many twists and turns — which is perhaps fitting, given the artist’s aversion to straight lines — Whangārei’s Hundertwasser Art Centre finally opened in February 2022.

Was really great to learn about this place Peter! As an ex-Whangarei resident and fan of the Kawakawa toilets, I wanted to visit here while staying in Amsterdam. But I didn’t make it (limited time, reliance on train, and quite a distance making it more than a day trip). Still, now my Amsterdam-dwelling Kiwi friends know about its existence, and I might make it next time.

I’m impressed you’d already heard of it. I only knew because of a random email from a Dutch guy who’d read one of my news stories about the Hundertwasser toilets in Kawakawa. Even my Dutch relatives who live nearby didn’t know about it.

This was an interesting read.

I’m from Whangarei NZ & think I had to be in a small group of firsts there to be a fan of Hundertwasser buildings. I even brought his wonderful book well before there was talk of a building of his in Whangarei.

I was therefore very disappointed to hear of their refusal at the time..and up to now I’d never heard of the offer to Wellington city of that project. What shortsightedness.

I was so thrilled for Kawakawa to have the beautiful toilets crafted which ended up bringing quite a change to the whole little town..it brought pride to the people & to have him alongside them on the project was pretty special.

Now..after much ado, & a few years of tacky red, yellow & blue coloured posts everywhere, Whangarei has its building but for me, as an anti-supporter I care less. ‘Why should we now have it & take away from Kawakawa their ‘pride & joy’ of being the only town in NZ to have a famous Hundertwasser. I saw it as stealing the show..the tourism & prestige from them..they honored Friedensreich & had him among them as family. AT LEAST they can say that their set of toilets was his final project. They are original: planned by him and constructed with him right there and present at the great ‘opening’ day in the year 2000. This was his final piece of art produced in his lifetime!

And because of the way Whangarei council have not told the whole truth, plus the fact it’s fallen on the people of Whangarei to cover costs in a time of financial strain..its of no excitement to me. Its a building without ♡..its not a true blue Hundertwasser nor directly linked to him as the Council profess. I don’t believe he’d even have given his signature of approval in the end!

Thanks Yvonne for sharing your Hundertwasser story. I haven’t seen the Whangarei building in its finished state yet; I’ll visit next time I’m in the city and make up my mind about it then. But as you say nothing can take away Kawakawa’s honour of having the last building Hundertwasser designed and worked on himself.